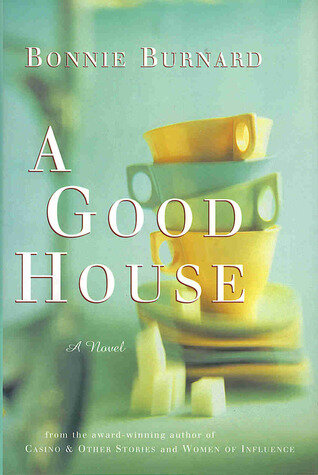

Bonnie Burnard: A Good House (Writers In Their Garden)

A garden promotes civility.

After she had made the necessary improvements to the 1950s ranch-style house she had bought a few years back, and after she had ushered her three children into secure young adulthood; after she had completed the manuscript for her first novel, A Good House, and after the novel, having earned the Giller Prize, had rocketed her into Canada's loftiest literary circles, Bonnie Burnard at last found the time, energy and inclination to tackle her extensive garden.

When she had first purchased the property in London, Ont., she hadn't given the garden much thought. Her attention had been focused squarely on the house itself: the location of windows, the height of ceilings, the potential of rooms. But later, surveying the perennial bed that splayed 150 feet along a brick wall in a broad corner lot - ''a good '50s lot'' - Burnard wondered if she was up to the challenge. ''Are you a gardener?'' a neighbour asked. ''We'll see,'' she replied.

Burnard detected among her neighbours a somewhat proprietary interest in her garden, which for years had provided them with a source of viewing pleasure. The previous owners had cultivated two to three dozen varieties of perennials, bright daffodils that shot up each spring and crimson tulips that stood out boldly against the cool, emerging green. There were black tulips as well, mysteriously romantic, and then, saucy poppies, and peonies so pink they looked closer to red. Some neighbours expressed a personal connection to Burnard's garden: once when she complimented a neighbour on her tulips, the woman said, ''Those were your tulips. The squirrels brought them over.''

Burnard has come into the kind of garden that stirs community pride, though she says the feeling is mutual: her garden enhances her neighbours' view and their gardens enhance her own.

''I'm grateful to my neighbours for my backdrop,'' she says. ''I'm reminded of a song by the folksinger John Hartford, who wrote Glen Campbell's Gentle On My Mind. Hartford sings a song about how 'your back porch looks out on my front porch.' What I am trying to say is: My yard isn't only my yard. You don't stop seeing at the property line.''

Community values flow through the novel A Good House like the creek flows through the fictional town of Stonebrook, Ont., where the story is set. A Good House refers to the solid, comfortable homes - and by extension the solid, warm families - that make Stonebrook a pleasant place to live. We are introduced to the Chambers family: Bill and Sylvia, and their children, Patrick, Daphne and Paul. The book eases us through the shifting seasons of the characters' lives. Burnard portrays an older generation nudging the next along and the younger generations leaning gratefully on the wisdom of their elders. In A Good House, family responsibilities transcend blood ties to meet neighbours' needs and civic concerns.

Burnard's emphasis on community values might strike some as outmoded or purely wishful. Yet in her own life she regularly encounters like-minded individuals. She could be one of the few gardeners inhabiting a town where the owner of the local nursery makes housecalls: ''I was worried that the ivy (Boston and English) climbing up the wall of my house was dying,'' she explains. ''He dropped by to have a look and assured me that everything was OK.''

Burnard has solved a number of gardening dilemmas herself. She cured the lodgepole pines outside the living-room window of inchworm: ''First I had to give them some poison. Then I had to give them some nurturing.'' She found out the hard way that if you transplant peonies they will not come back the following year, though they will return eventually. Burnard has discovered, to her everlasting bemusement, that ''You can't insult perennials. You can dig them up, split them, transplant them - and they just keep going!''

Despite her steady acquisition of gardening know-how, Burnard laments what she describes as her ''steep learning curve.'' She welcomes her neighbours' helpful advice, not to mention their regular acts of kindness. A 70-year-old neighbour was quick to respond when a summer storm toppled her ancient walnut tree. ''The tree was by the back corner of the garage, Burnard says. ''I didn't even know it was down. I just heard his power saw.''

Burnard has twice been required to have trees chopped down: an Austrian pine that was planted too close to the house, and a maple to accommodate the widening of the street. Both times she drove 90 kilometres to her father's place on Lake Huron to avoid witnessing the destruction of a tree.

With the money the city gave her to replace the maple, Burnard planted, along the side of the property, an English oak, a white spruce, and another maple - one with burgundy leaves.

''I look at those three trees through a window with a window seat,'' she says. ''And sometimes I think the remaining span of my life will be measured by those trees.''

Burnard believes that a good house, in order to be a good house, ought to contain a room with a view. She is conscious of using her kitchen window to frame a picture, moving some plants that were growing next to the house over to the garden wall: ''I wanted them in the perennial bed,'' she says, ''so that I could see them from my window.'' A euonymus hedge that was blocking her view of a 50-year-old Schwedler maple was ripped out.

From her kitchen window Burnard can admire a forsythia two back yards away. ''As soon as that forsythia goes yellow,'' she says, ''I know that it's spring. My neighbour's garden is part of my picture. I see beyond my own yard.''

This piece previously appeared in the Montreal Gazette in 2001.