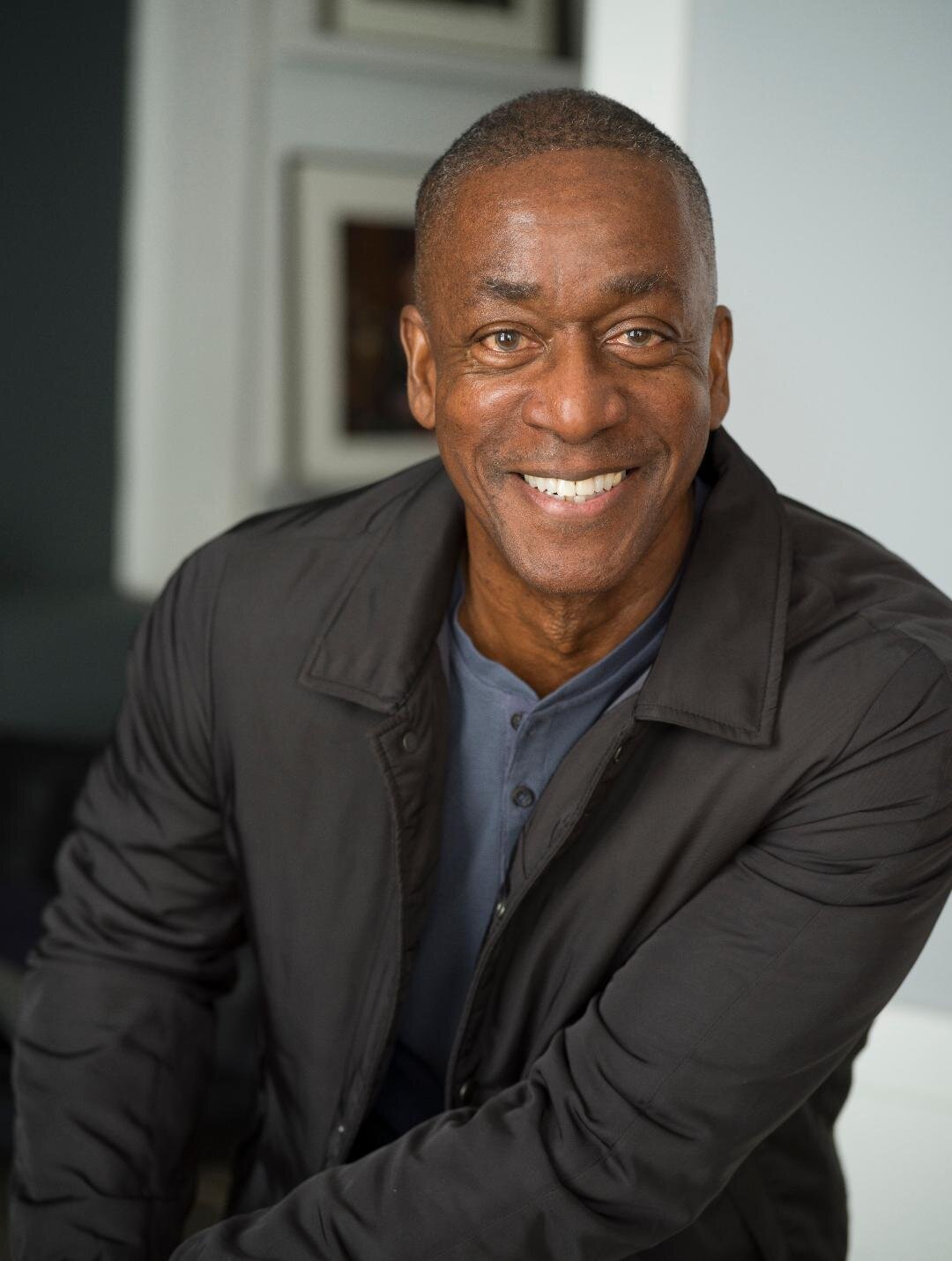

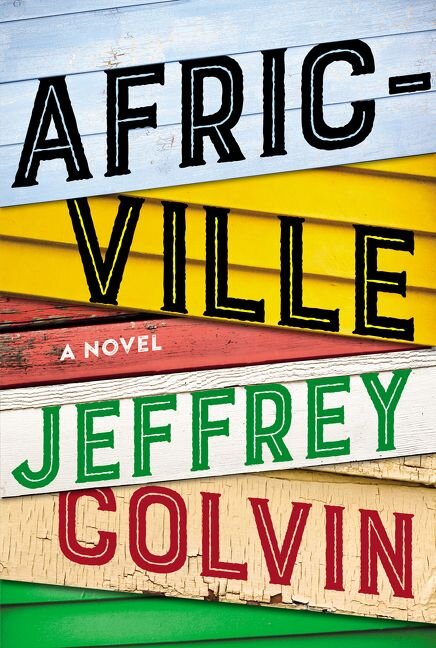

Jeffrey Colvin's Africville: Stories of Resistance Part 1

Jeffrey Colvin grew up in the segregated Montgomery, Alabama of the 1960s. Respect and affection for his black community profoundly informs his extraordinary debut novel, Africville. The novel is inspired by the African Canadian village on the edge of the Bedford Basin that was demolished by the city of Halifax in the late 1960s. Africville’s fate resonated with Colvin who witnessed scores of black southern towns erased by gentrification.

The novel follows the life of Kath Ella Sebolt and her family, including the ancestors who helped settle the community and the descendants who eventually depart, some of whom pass for white. He paints a vivid, bustling portrait of a black community, then contemplates the meaning of its demise. The main action of the novel spans the twentieth century and travels from Eastern Canada to Alabama and Mississippi. It is prescient in its depiction of an epidemic that strikes the black community; and also in its portrayal of racist police violence in Canada as well as in the American South.

In Part One of our in-depth conversation Colvin discusses the legacy of his segregated past, the relationship between North and South, and the emotional impact of the death of George Floyd.

DBN: As black Canadians we rarely encounter African Americans who are fascinated by black Canadian experience. Why do you think you are different in this regard?

Montgomery, Alabama 1960

JC: Attending events in the United States to promote my novel, I have met many African American readers who are fascinated by the lives of blacks in Canada. What has been lacking has been efforts by publishers to bring the stories of blacks in Canada more widely to readers here in the United States. I am glad to be a part of an effort to do that. As for my interest in the lives of black Canadians, I spent my childhood in all-black communities in the southern United States, and I attended an all-black elementary school. Despite segregation, during my childhood, I felt supported and valued—and encouraged to wonder about places beyond my neighborhood. One question I remember asking is why neighborhoods in Alabama were segregated. If people were the same as I had been taught--why did blacks and whites live in separate communities? And I wanted to know why did the houses, the schools, and the roads in black communities seem to be of lesser quality than those in white communities? At the Naval Academy and in the Marine Corps, I met men and women from all over the United States, and a few from Canada! I lived overseas in communities, which at first seemed vastly different from communities in which I grew up. But eventually I came to see the many ways these communities seemed familiar to me. Discovering connections between black communities in the US and those in Canada made my research into the community of Africville very exciting.

DBN: How did this story come to you and why was it so important for you to write it?

Africville, Halifax, Nova Scotia 1965

JC: Africville began as a series of short stories written in the late 1990s. These stories were set in a rural black community in central Alabama like the one where my grandmother raised a family. After I graduated college, I came home to the news that my grandmother had moved out of the community, and the last houses there had been abandoned and torn down. Many of the stories told by my grandmother and her former neighbors about their former community where happy ones. But there were also unhappy stories such as the lack of adequate resources for the small public school, and the difficulties the young men and women from the community encountered when they searched for jobs after the coal mines closed. I did not envision any of the stories I was writing as part of a larger narrative until I read an article in the New York Times in 2001. I had no idea that a black community called Africville had once existed on the northern edge of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Nor had I known that Africville had been in the headlines in the late 1960s when, over the objection of the residents, the city of Halifax bulldozed the homes and the community church to make way for a bridge entrance and a city park. Reading the article, I was moved by how vociferously the residents had protested the destruction, and their decades long fight for restitution. With further research I began to see connections between the story of Africville and the rural communities I was writing about. There were stories of individual successes, and of strong family and community ties along with stories of struggles against racism and oppression. I was soon convinced that characters from a town like Africville could be the source of a very compelling novel.

DBN: How has the murder of Floyd affected you as a black man from the South?

JC: Like many people all over the world, I am dismayed by the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many other black residents at the hands of police. Unfortunately, as a black man whose childhood in the Jim Crown South included daily reminders of America’s racist structure, I was not surprised. George Floyd’s death strengthened my conviction that those speaking against racism must do so even louder.

Writing about the pernicious effects of structural racism has always been important to me. It’s a tendency that goes farther back than I sometimes remember. Just this week, I received a notebook from a former classmate from the Naval Academy that contained a poem I wrote over forty years ago. The poem, titled, Busy Makin’ Black, contained these lines. Steady makin’ braids/Dodging police raids/Someone tell me when/will it flash/ “end.”

The poem ends with the question: ‘Know I’m gonna die, but/when?

George Floyd

Ironically as a student at a military institution that prepares young men to go to combat, I was not compelled to write about how I might die at the hands of some enemy soldier overseas. But I did fear that I might perish at the hands of a policeman in my own country.

I believe memories of the inequities I witnessed during my childhood in the segregated Alabama, led me to write essays and reviews on books on the work of black writers, particularly those that explore the effects of racism. My essay in the Brooklyn Rail referenced the murder of Trayvon Martin to discuss the work of the activist writer Ishmael Reed. I also wrote numerous reviews highlighting black authors for Narrative Magazine, including Edwidge Danticat, Edward P. Jones, Zora Neale Hurston, and Marita Golden, whose, powerful memoir, Don’t Play in the Sun, explores the harmful effects of colorism.

Rosa Parks

Africville grew out of a story of resistance that made headlines nearly twenty years ago, however, many of the novel’s main events are relevant to resistance stories in the media today. The novel begins in 1918 with the community besieged by a mysterious illness. This opening was based on the early twentieth century outbreak of influenza, a malady which, like COVID-19, had no cure, and which had a devastating effect on black communities. Early in the novel, Kiendra Penncampbell, a young resident of the community is unjustly killed in an encounter with the police. Zera Platt, a black defendant in Mississippi is given a harsh treatment by the courts and serves an unjustly long prison sentence. And finally, Africville presents numerous protest--whether near Montgomery, Alabama or Halifax, Nova Scotia--against the racist treatment of black residents. Unfortunately, stories of members of the black communities protesting inadequate health care, police violence, and unfair treatment by the criminal justice system are headlines still with us today. Given my personal history, I will continue to incorporate these issues into my writing for some time to come.

DBN: I know it took a long time to finally bring the book to publication. Can you describe the process of researching and writing Africville?

JC: It took twenty years. The novel has a lot of moving parts—a wide geographic scope, a large cast, and a lengthy span of time. Early on, I visited Halifax to experience the sights, sounds, and smells of the land on which the village of Africville once sat. Meeting former residents of Africville and their descendants, I was struck by how welcoming they were. I was a stranger from way south of the border, asking questions about their former village and yet they welcomed me as if I were a returning son. A gentleman at the local library who had relatives who had lived in Africville offered me a treasure of photographs. I also studied articles, films, and books about the founding of Africville in the late 1700s, its destruction in the 1960s, and the protests that spurred restitution efforts by the city of Halifax in the 2000s. The other settings of the novel--Montreal, Toronto, Vermont, rural Alabama and Jackson, Mississippi--were locations I had visited or lived.

The novel spans a shorter period than the scope of my research, its scope is wide nonetheless, beginning in 1918 and ending in the early 1990s--seven decades. Capturing the look and feel of those early periods required many hours in the library. Although a bit of aimless wandering among dusty archives and side trips on the internet led to a few pleasant discoveries, I kept my focus by daily reminders of the types of information I wanted to include in Africville.

Africville, Halifax, Nova Scotia 1965

Presenting a large cast of characters was challenging. I consulted books , read, and attended plays, watched movies, and drew on the many people I have met over the years. By the mid-2000s, I had a general outline of the narrative and any newly discovered historical details were incorporated into the novel as appropriate. At about the fifteen-year mark, I stopped doing research. By then I had been writing fiction for over a decade, so I felt comfortable believing in the narrative and following the story as it developed. I also felt comfortable straying from historical accuracy of the village of Africville. It is fiction, but more importantly, given the powerful way the people connected to Africville told their stories I felt no desire to duplicate them. I consider my rendering of the village of Africville as a complement to those powerful stories.

DBN: Can you talk about your life with your family growing up in Alabama? Are you the first writer in the family?

JC: I am the middle child of five. I recently lost two sisters to cancer and now have a brother and sister. I am still the middle child. My parents divorced when I was a child, and I was raised by my mother who worked numerous jobs including a few low-paying ones for the state of Alabama. My mother did not directly encourage me to become a writer, although she would show me her college papers and she recited poetry by black writers as many parents I knew did.

DBN: Were you a contented child?

JC: Probably not. As I mentioned, even as a small child I recognized the inequities under segregation. My escape was reading. In school I liked history, math, and music. I also enjoyed hearing family history but wanted to travel beyond the South. I drew on this desire in crafting the early life of Africville matriarch Kath Ella who wants to travel not just to places in Canada but to farther places like France and Morocco.

DBN: Were you always a great reader? If so, what did you like to read as a young person?

JC: My grandmother and my great grandmother read the newspaper every day. My mother would come home from work, fix dinner, then lose herself in a book or a popular magazine. I read children’s books and began reading newspapers even before I fully understood all that I was reading. This habit of reading challenging texts continued into junior high school where I would check out novels from the school library to read on my own. At that age I did not fully comprehend the depth of a novel like The Brothers Karamazov, still I struggled through it because I enjoyed reading.

Part Two of Jeffrey Colvin’s Stories of Resistance to follow.