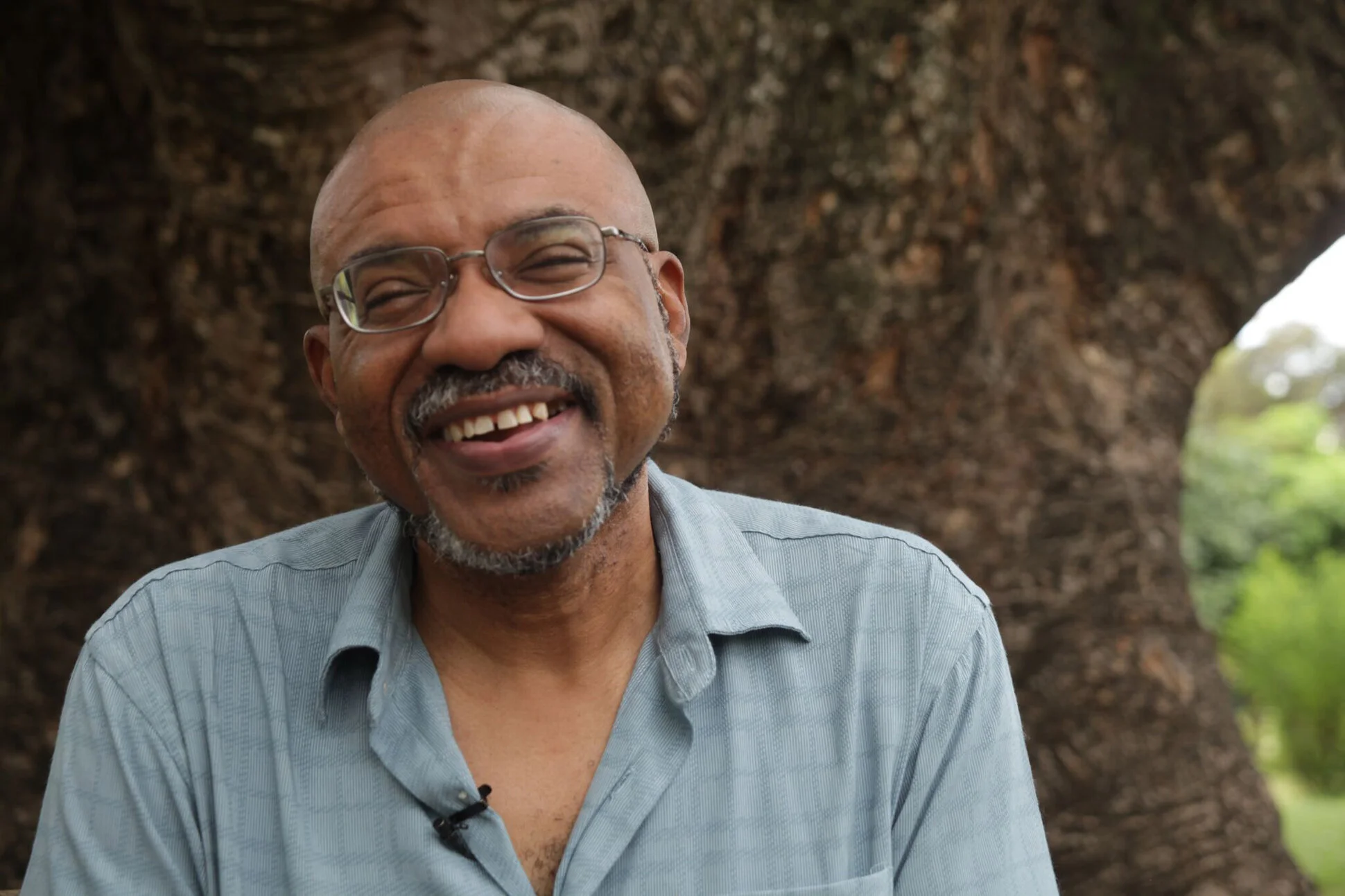

Jeffrey Colvin's Africville: Stories of Resistance Part 2 (Black Lives Matter Series)

This is part two of my interview with Jeffrey Colvin about his novel Africville which was inspired by the African Canadian village in Nova Scotia of the same name. Africville was demolished by the City of Halifax in the 1960s. Colvin draws an analogy between the village’s erasure and the disappearance of black towns in the Deep South. In Part Two Colvin delves into his ideas about black Canadian literature and discusses his unique, somewhat idiosyncratic literary style.

DBN: You have worried about small black towns in rural Alabama being lost to gentrification. Why are these towns so important to you? What are we losing culturally speaking?

JC: The exodus of blacks from neighborhoods and towns which I first witnessed in the south I would see again as an adult. The Western Addition in San Francisco, Anacostia in Washington DC, and Harlem in New York were communities with rich histories. However, by the time I arrived these communities were threatened by a rapid exodus of black residents due to gentrification. In these communities I met many former residents who had returned for a visit who exhibited a sense of loss. Sometimes they told stories of people who had been forced to leave seeking better living conditions, and other times there were stories of neighbors who left because they were offered exorbitant monies to sell in an overheated housing market. Invariably when former residents returned to their neighborhoods, sometimes with their children, they told of the fondness they felt for the old neighborhood and the great loss they felt. This was no mere nostalgia, but a profound sense of knowing it did not have to be.

DBN: Did you draw upon your grandmother’s life for the character Kath Ella?

Africville, Halifax, Nova Scotia 1965

JC: My three sisters and my mother were probably the greatest influences. I used aspects of what I observed watching my sisters to create Kath Ella as a teenager, everything from what she might wear in different situations to how she interacted with the children in the neighborhood, her parents and teachers. I drew upon the stories my mother told about her college experiences and I examined her college papers and books to craft various scenes with Kath Ella in college. To write Kath Ella’s relationship to her son during her illness, I drew up memories of my sister and her relationship with her daughter before my sister died from colon cancer. Some of these memories came with pain, but I believed they helped me develop one side of Kath Ella as an older adult.

DBN: Kath Ella and her best friend Kiendra seem to be parallel figures in the novel.

JC: Kath Ella and Kiendra have different strengths and challenges. As teenagers each presents her smarts to the world in different ways. Kath Ella is bookish, but not always able to read people well. I find it intriguing that she does not exhibit a strong desire to recognize this part of her personality. This is understandable given how focused she is with certain aspects of getting ahead in the world. Kiendra is a talented singer and has a quick mind, however, she does not exhibit her smarts in ways that are often acknowledged by her family, teachers, or members of the community. Much of Kiendra’s wonderful writing as a teenager, for instance, she keeps to herself and it is discovered later after her death. Kath Ella and Kiendra experience racist actions at the hands of whites, but for Kiendra, an adult whose mind is still impaired from a childhood fever, the outcome is more tragic. I find Kath Ella a wonderful character, but I am grateful to be able to discuss Kiendra because her unfortunate experiences help the reader understand how undiagnosed mental impairments affects residents of black communities besieged by poverty and police violence.

Montgomery, Alabama 1960

DBN: One of my very favourite aspects of the novel is the significance placed upon objects like buttons, rocks, ribbons, letters, even floor planks or entire buildings. Why are objects so significant in Africville - the place and the novel?

JC: On a practical level, physical objects are the connective tissue of novels. They carry personal, family and community history—all important aspects of the story of Africville. Some physical objects like the rocks which Kiendra collects and the buttons on one of Kath Ella’s suit may be important for mere months or years, while other objects like the floor planks from a backyard shed in Halifax, a gold bracelet an imprisoned mother promises to her son in Mississippi, or the apartment number on the door of a Montreal apartment may link characters and lives over decades and generations.

DBN: Most black fiction encourages us to look backward. In contrast, your work has a very strong forward motion. How come?

JC: One of the things we recognize when we endure a painful loss is our resilience and our ability to move forward, carrying hurt but also, in many ways, more strengthened. I did not understand this aspect of life until I became an adult and began to lose close members of my family—two sisters and both parents in less than four years. Africville has been called a challenging novel. Some readers say they eventually appreciate the journey of becoming comfortable with the use of the present tense. This artistic choice reflects my attempt to present the notion that the main elements that propels the novel-structural racism—is not an historical fact, but a constant element in North America. Even as time moves forward there is a weight to the present. Also challenging is the way I expand the narrative in places to deeply explore certain events. Africville is not a page turner but many readers appreciate the powerful movement inherent in the way these explorations connect to the novel’s themes of loss. I hope Africville is a novel that reveals new powerful ideas with each re-read.

Montgomery, Alabama 1960

DBN: Kath Ella’s son Omar is so fair skinned he decides to pass for white. Why are the themes of biracial identity and passing central to the story you want to tell?

JC: Early in the process of writing this multigenerational story, I knew what forces might move members of the Sebolt family toward cherishing the town where their ancestors lived including its unique history and the continued efforts by its former residents to keep the town’s memory alive. But I struggled with the question of what forces would pull them away from a connection to Africville. Kath Ella’s estrangement from her community begins when she moves with her son, Etienne to Montreal. As a teenager, Etienne struggles to accept his blackness while having his blackness questioned by some of his school mates. He arrives in the United States believing that presenting himself as white offers more opportunities than presenting himself as black. He later moves to Vermont and then to Alabama where his son, Warner, grows up unaware that he has a black grandmother. Creating Etienne and Warner allowed me to explore many intriguing questions. What might lead a person to decide to pass? Under what emotional toil might they struggle after the decision has been made? Etienne’s struggle after deciding to pass is an internal one that strains his interactions with his wife, his work colleagues, the residents of the rural Alabama community where he settles, and especially his son. Warner learns as an adult that he has a black grandmother who was raised in Africville. He wants to connect with former residents of Africville but they are hesitant to accept him given his father’s previous estrangement from the community. The decisions Etienne and Warner make about whether to pass for white demonstrate the powerful way our identity can complicate our lives. They also reveal that many of the internal and external struggles characters have around their racial identity can exist whether the character is living in what is thought of as the liberal and progressive North, including Canada, or the conservative South.

DBN: Omar’s paternal grandmother eventually spends more than 60 years in prison in Mississippi for her part in a protest. Can you talk about the sickening dilemma of black senior citizens wasting away in American prisons?

Rosa Parks

JC: I first read about the horrors of the way blacks are treated in the justice system when I was researching how trials were conducted at the turn of the century. I was surprised to learn how summary many trials were, some lasting mere minutes, despite resulting in very harsh judgements. The poor were especially disaffected during this era and, especially blacks. When I first conceived the idea of Zera Platt serving an inordinately long prison term, I thought it would be difficult for readers to believe that there would not be earlier avenues for her parole. But as I began to research the way the criminal justice system has treated blacks from the early 1900s to the early 1990s, I found that scenario all too believable.

DBN: Much of the book unfolds in the Deep South in the early decades of the 20th century and yet slavery is barely mentioned. Why is that?

JC: Slavery, like racism is a charged expression whose manifestation has been explored from many angles and rightfully so. What I was interested in were the lasting effects of slavery. This included the lack of opportunities for blacks in the south, their being relegated to having lesser access to educational, economic, and housing opportunities than whites. When I grew up in the 1960s in the American south, most of the people I knew were interested in the ways in which their current lives were impeded because of the color of their skin. This was the case for the characters who were visibly black. But since racism works beyond the notion of skin color, I wanted to explore how it affected characters who do not appear as what is traditionally termed black. And I was interested in the ways in which racism affects whites in the south. The lasting effects of slavery impedes the lives of black and whites.

DBN: You have a very unique style that tends to slip characters into a crowded canvas with very little fanfare. In fact they feel very Mexican to me, like the murals of Diego Rivera or the novels of Carlos Fuentes. Can you share a little more about your technique?

JC: While Africville is about a group of characters from a specific place, one major element of the novel is the way these characters interact with each other and even more importantly, how they interact with the world outside the village. One way I explore this is through an interest in the events that bring people together. How stranger and acquaintances interact in familiar and new circumstances is always interesting to me. And I am interested in exploring how people come together, sometimes through uplifting events like parties and graduations, but also through sad events like departures or funerals.

DBN: New York has been devastated by the Covid 19 pandemic. How has it impacted your life?

JC: After Africville launched in early December and I completed most of the stops on my tour between December and February, including well attended events at public libraries in Princeton, Boston and Toronto, and the Center for Fiction in New York. However, this past spring quite a few events were cancelled. And like many writers, I am working hard now to continue to promote the book in these difficult times. While it may be doubly difficult for a debut novelist to be heard in what I consider to be a global conversation on structural racism, I strongly believe Africville can be a part of this conversation. It is important to talk about structural racism in essays and history tracts, but there is equal power in experiencing the deep effects of racism on people. Such experiences can be powerfully rendered through a novel.

DBN: What have you been reading and writing during this period and why?

JC: I am working on another historical novel, so I have been doing research. I am chest deep in articles, books, and other sources about the European and black presence in the Americas in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. But I can only do so much research online. I recently received a fellowship to conduct research at Brown University, and I am hoping to be able to continue my research there this fall. A lot, however, depends on the safety of the campus given COVID-19.

DBN: Thank you so much for this, Jeffrey.

JC: My pleasure.