I Remember Papa

I went to visit Rachel Manley one afternoon at her home in Toronto. It was a brilliant day. The afternoon sun spilled through the kitchen window, trailed through the dining-room and formed pale shadows in the drawing-room beyond where Manley lay stretched out on a plump white sofa, a heavy quilt pulled up to her chin. She explained to me the furnace was giving trouble and that she felt cold. But one could also see that she was tired. The festivities of the previous evening had left her drained.

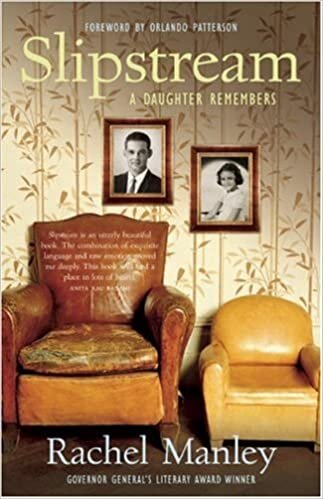

The night before, her book Slipstream: A Daughter Remembers (2000), had been launched at Toronto’s Arts and Letters Club. Slipstream is a memoir, a poignant chronicle of the loving, conflicted relationship she shared with her father, former Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley. Manley died of cancer in 1997 at the age of 72. Rachel began writing Slipstream during the final months of his life. It is the second installment in the trilogy that begins with Drumblair: Memories of a Jamaican Childhood, her personal recollections of her grandparents, Jamaica’s first premier Norman Washington Manley and her artistic grandmother, Edna.

Among the crowd of well-wishers at the Arts and Letters Club an attitude of reverent nostalgia prevailed, vanquishing, for the moment, lingering bitterness about Michael Manley’s socialist policies. During the 1970s those policies had led many Jamaicans to flee the island for dubious comforts abroad. Rachel read aloud from her book with Granville “Jack” Johnson, her father’s trusted comrade, by her side. When she momentarily lost her place, Johnson broke into a rendition of “Jamaica Arise,” as he had so often done in her father’s day:

The trumpet has sounded/ My countryman all/ So awake from your slumber/ And answer the call.”

His listeners joined in, their voices thick with longing, pride and regret.

“The torch has been lighted/ The dawn is at hand/ Who joins in the fight/ For his own native land.”

“Last night wasn’t business as usual,” Manley whispered from her cocoon on the couch. “I didn’t feel like it was a do that had been put on and that people were attending. When Jack stood there and sang…I could just remember the whole 1970s, the elections and all the hope. The evening was so emotional for me.”

And lonely. Gone is the trinity of loved ones – her grandfather, grandmother and father- who for so long formed her emotional foundation. The most meaningful ties to her past have dissolved. These days, Manley admits, “I feel like I’m in a pool and I can’t feel the bottom.”

The book launch proved especially difficult. “I don’t think I’ve ever missed those three giants like I did last night,” she said. “Just missed them. Missed them so much. All three of them. I felt this huge loneliness.”

Michael Manley

Rachel Manley seems ageless in a Peter Pan sort of way. She is petite, a sprite and seems light enough to defy gravity. She speaks with startling poetic candour and exudes such immediate warmth that I am surprised when she confides that loneliness is a feeling she has struggled with all her life. She attributes this to being separated from her mother, the first of her father’s five wives, at an early age. The marriage ended when Manley was a toddler. Mother and daughter did not meet again for 14 years.

“When you lose a mother at two,” says Manley,” I think you are left with a slightly bereft feeling that you can’t quite put your finger on. I’m always amazed at how many people wake up happy first thing in the morning. My waking up is always a process of getting busy so I don’t brood.”

Despite the devotion of her grandparents, Manley grew up perpetually lonely for the company of her father. In Slipstream Manley recounts her heart-wrenching efforts to hold his attention. But her father’s climb to power – his heroic labour negotiations, his election to national office and the tumult of his political life- precluded the kind of father-daughter relationship Manley craved. What personal space he allowed himself he committed largely to romance. Rachel found herself eagerly awaiting his down times: “In a funny way, all my life, whenever my father was ill or heart-broken or defeated by an election that was when I got him back. As I say in Slipstream. ‘His troughs became my pinnacles.’ ”

It is a sad irony that the longest uninterrupted stretch Manley spent with her father occurred during his last months. Prostate cancer had left him bedridden in his unassuming Jamaican townhouse. Manley rarely left his side. Although she had originally set aside those weeks to work on her grandmother’s biography, she realized that her father’s story would have to come first: “I was just washed in the pain of my father (and) I gave into it. I went through my old routine: when I woke and felt the pain, I just went to work and within five minutes of beginning writing, I feel no pain. I am just weaving.”

In Slipstream Manley expertly conveys the force and nobility of her father’s character, even while he lies helpless in bed. Though the life seeps from his body, he remains “Michael Enormous,” his spirit looms large. She also magnificently renders her own sorrow, which, by the end of the book spins out into terror and rage. The final pages are a truly harrowing expression of grief.

“That was the bit that I wrote when he was still alive, when he was dying beside me,” said Manley, her voice breaking slightly. “Not a word of it has been changed. From where it said, “Go to sleep, my beloved father, go to sleep. This is winter in the mountains.’ I wrote that sitting beside him. What else could I do? I just sat there writing.”

From What’s a Black Critic To Do? Interviews, Profiles and Reviews of Black Writers