Cherie Jones’ Spectacular Year

Cherie Jones’ Spectacular Year

The author talks about gender roles, domestic violence, and the dangers of Paradise

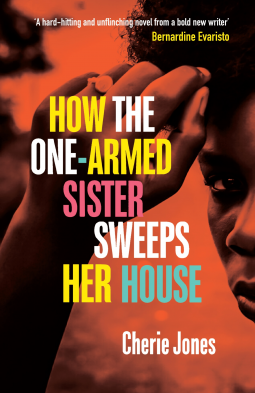

Barbados’ Cherie Jones is having a spectacular year. Jones is the author of the hit debut How the One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House which Oprah’s Magazine called one of the most anticipated books of the season. In February, Good Morning America selected the title for its book of the month club. Most recently, One-Armed Sister landed on the longlist for Britain’s prestigious Women’s Prize for Fiction. The story unfolds in Barbados in the early 1980s, where a wealthy white tourist is murdered in his vacation home on a heavenly stretch of beach. A local young woman named Lala is married to the murderer. She is trapped in a cycle of domestic abuse. Let’s just say this is not your typical depiction of a Caribbean paradise. Says Jones: “What we have is two bubbles co-existing- the tourists and the locals. I wanted to talk about what happens when those two worlds collide.” Jones, a lawyer, previously won a Commonwealth Writers Prize for her short story, “Bride.” She spoke to me over the phone from Barbados where she lives with her four children.

***

DBN: Congratulations on your success! How are you handling everything?

CJ: Thank you! It’s exciting - and a little overwhelming. A dream come true.

DBN: How have readers responded to the book?

CJ: People have told me they cried. Others said they were so angry they wanted to choke Adan (Lala’s husband). Some found the topic of domestic abuse so hard, they had to put it down. One friend at work was mad with me: She wanted the ending to be kinder. (Laughter)

DBN: Your book’s unusual title comes from a folk tale told to Lala by her grandmother about an obedient sister who follows the rules and a questioning sister who winds up injured when she goes her own way. Were you told this tale when you were growing up?

CJ: How the One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House is not an actual folk tale. I made it up. In Barbados we do have the tradition of oral storytelling and of using scary tales to warn children away from places we don’t want them to explore. We have monstrous characters like the Bacoo conjured by our parents to scare children away from particular places and particular behaviours.

I chose this title because it immediately informs the reader that the novel is grounded in a domestic sphere. The story basically answers the question posed in the title: If you are a woman and you are being judged in this domestic sphere, and you are suffering in a situation that makes you less than able, how do you live up to expectations?

DBN: The folk tale involves a good sister and an “own-way” sister. Which one are you?

CJ: I am both. We are all on a continuum of good and bad, and where we are is a product of our experiences. I explore that duality throughout the novel. For instance, living at Baxter Beach is for some a very luxurious experience and for others it’s a very disadvantaged experience. The town of Baxter itself has beautiful pink beaches, and also dark, dangerous tunnels. For humans there is the same complexity: At some points in my life I’ve been the “own-way” sister – the one likely to go into the tunnels.

DBN: Lala is raised by Wilma, her overbearing grandmother. But on her 13th birthday she suddenly comes into her own.

CJ: Yes. On her 13th birthday Lala really starts to become who she will be - and less of everything she’s been told to be by her grandmother. There is a point in your life when you start to question. Prior to that it’s pure mimicking of our elders. At the same time, Lala’s grandmother is the one who gives her a mannequin’s head for her birthday, which is an acknowledgment that Lala excels at doing hair. It is that mannequin head that gets Lala thinking about braiding hair for a living and escaping Wilma and Wilma’s particular brand of wisdom.

DBN: Wilma raises Lala to be modest and accommodating, even though this would seem to go against Lala’s assertive nature.

"We are all on a continuum of good and bad."

CJ: There’s a very strong sense of the expectations of gender in Barbados and how gender is to be performed and understood for females. This is something inculcated from a very young age. Girls are encouraged to be modest and not to shout or be too outspoken, which is taken as an affront to males. I experienced this as a girl, and later as well. I am a single mom of four and there were things that I have wanted to do that would be frowned upon even for an adult female -things my brother would be able to do. When I complained about this to a male relative he said, “The boys don’t bring home the babies.”

Lala’s grandfather is a terrible person. Still Lala sees Wilma give him pride of place. That is part of the gender positioning. Wilma is a product of her time.

DBN: Lala’s husband Adan, is not only a murderer; he is a vicious husband. You depict domestic abuse as pervasive.

CJ: It is so entrenched an understanding of the role play between women and men. Men beat women. It only seems to become a problem when a woman dies. Then people say, “He stepped over the line.” People will often say a woman knew her husband was crazy when she married him. In other words, a woman is assaulted and then blamed for the assault. This was something I wanted readers to explore. I wanted them to talk about how we feel about this type of behaviour.

DBN: You are also a survivor of domestic violence. Did that make it difficult for you to write the book?

CJ: It was difficult to write the book. But it was also empowering. I really wanted to address how we talk about violence. When I describe the violence that Lala suffers, I look at who and what is impacted and less at the gore. I want people to focus on the psychological impact it has on the person and the community and the region.

A lot of times people use verses in the Bible to justify the placement of women as inferior and submissive to their husbands, or any male. But in the scene where Adan reads the Bible, just before assaulting Lala, I focus less on the violence of his reading and more on a cup that falls and all the other things that are happening in the room around the assault. I felt somehow, if I fully reproduced the violence on the page, it would be as though Lala was beaten up twice.

DBN: A number of the men in the novel are physically and sexually abusive. Have you had any complaints about your characterization of them?

CJ: I haven’t had any feedback about that. But there are also some beautiful male characters in the novel. Adan’s friend Tone is the embodiment of love. And Peter, the tourist Adan kills, is also lovely. There are beautiful male characters and there are hard male characters. It is just that the actions of a man who is not so good becomes the focal point of the story.

DBN: Lately, I have been reading a fair amount of contemporary Caribbean fiction – including Nicole Benn’s Patsy and Here Comes the Sun. In these stories I find a pattern of women failing their daughters and granddaughters. This is true in the One-Armed Sister. Wilma will not allow her daughter Esme to return home, even though Esme is being beaten by her partner. She turns her back on Lala, as well, after Lala marries Adan. That makes me mad. I can’t let her off the hook.

CJ: The mothers and grandmothers are themselves the product of social conditioning. It is difficult for them to model something different than what they’ve been taught. They are not self-aware. You know how the saying goes: “Hurting people hurt people.”

DBN: The murder of the rich white tourist is just one of a handful of occasions in which you thwart our expectations of a Caribbean Paradise. Why?

“I felt if I reproduced the violence on the page, it would be as though Lala was beaten up twice."

CJ: What we have is two bubbles co-existing - the tourists and the locals. I wanted to talk about what happens when those two worlds collide. Peter (the tourist) is enjoying a wonderful vacation with his wife and children, and then one of the island inhabitants robs and kills him. It’s only when two world clash that we get an impression of what the difficulties are. There has to be that penetration – that removal of the veil. Why do we have different experiences colliding? Because we want that bubble to burst.

DBN: There is a beautiful moment in the novel- a kind of a pause- when the beach is quiet and still, and Adan’s friend, Tone, recalls a time when the fishermen used a conch to alert villagers that their catch was ready.

CJ: Yes. That’s a nostalgic moment. We are looking at the area in the mid 1980s – about 20 years past Independence. There has been a lot of development since then, and it did mean a loss in some parts of the island of a former way of doing things. On some parts of the West Coast you might still have the fish market. But you don’t have the fishermen’s announcement with the conch shell.

DBN: Do Bajan’s mourn that past?

CJ: I think for most locals, tourism presented an opportunity for personal advancement as well as for economic advancement. However, if we are so dependent on tourists, situations like COVID can be devastating. Thousands of people who work in the tourism sector are now suffering.

DBN: Did you grow up near the beach?

CJ: When I was small we lived in St. Philip very close to the beach. I remember that time of my life with fondness. I had a special feeling for the sea. I can remember from when I was very young, taking walks on the beach with my Dad. I also remember being inside our house, sitting on the bright orange couch, and waiting for my mother to finish stewing Bajan cherries for me. And her putting them in this green glass dish- a rich, red cherry compote -and me feeling like the most loved child in the world.

This interview took place on March 5, 2021.