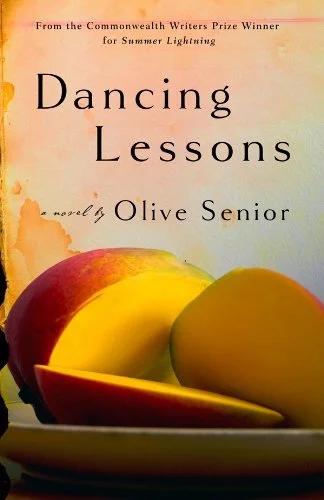

Dancing Lessons

Dancing Lessons

By Olive Senior

A stirring passage in Olive Senior’s haunting first novel, Dancing Lessons, depicts the wordless, mesmerizing courtship of Gertrude, the story’s heroine. Gertrude, a lonely, emotionally neglected teenager, is being raised by her grandmother and aunt just outside Kingston, Jamaica. The family are light-skinned blacks, members of a respected country clan that prizes their fair complexion above all. They are so cold and uncommunicative that several years elapse before Gertrude even realizes she is the illegitimate daughter of the shellshocked veteran who wanders in and out of their lives. Gertrude is the product of his scandalous affair with a dark-skinned woman, who passes away when she is small.

Gertrude’s primary pleasure comes from her weekly jaunts to the local shop where she spends her meagre pocket money on mouth-watering sweets. One day she notices a man eyeing her from across the street. She recognizes him as her father’s distant cousin. Sam Samphire’s penetrating gaze suffuses her body with heat. After that, he appears most weeks, although they never exchange a word, and their eyes barely meet. One day he arrives on horseback, sweeps her off her feet and gallops them off to a new life. She is 15 years old.

This breathtakingly romantic episode is by no means typical of the atmosphere of the novel. Taken as a whole, Dancing Lessons, which recounts Gertrude’s long, arduous existence, emanates a gothic air, representing the life of a Jamaican woman with dark fidelity to the island’s harsh history.

Gertrude’s Sam proves to be an inveterate womanizer. The couple can barely scrape enough together to feed their growing family. When a wealthy white pastor and his wife offer to give their daughter Celia a comfortable home and good schools, Gertrude and Sam hand her over. Celia is six years old.

Celia’s departure devastates her siblings and so does the sudden disappearance of Sam, who abandons Gertrude to move in with another woman. The loss of their sister and father traumatizes the three remaining children. But a bitter Gertrude neglects to explain what has happened. Says Gertrude,

“Didn’t I of all people know the awfully destructive power of silence? Yet I silenced my own children with a look, forced their own words back inside them with a hand raised to strike. For I hit them, O yes, and don’t tell me anything now about child abuse and cruelty. What did people like us know?”

Gertrude has no idea how to communicate, or how to mother, or how to express love. It is to Senior’s credit that the emotions she arouses in the reader are as complicated as Gertrude herself.

The novel is structured largely as a remembrance of things past in which the aging Gertrude looks back over her troubled life. She resides at a retirement home where she feels mistreated by the matron, is suspicious of her housemates and seethes with resentment for the daughter who has placed her in the home. We soon learn, however, to take Gertrude’s comments with a grain of salt.

Still, it is almost a relief to know that Gertrude- so put-upon in life- develops into an unsympathetic old woman, a true curmudgeon, insecure, but feisty. At the retirement home, she pilfers pens and mangoes. She is reprimanded for accosting an unsuspecting resident and forcing him to dance. She invents cruel nicknames for her wealthy, fair-skinned housemates, whom she believes only accept her because her daughter is wealthy and fair-skinned too.

Olive Senior

Class and colour are the pernicious facts that have defined Gertrude’s life. As a child she despises her crinkly hair, muddy eyes and fleshy nose, so different from the features of her father, grandmother and aunt. “To this day,” says Gertrude, “I have no idea if as a child I was really ugly or beautiful, for I had no one to tell me.” Of course, her black mother might have taught her to love herself, and to see herself as beautiful. But her black mother is dead. For Senior, as for many other Caribbean women writers, the absent black mother represents the absent black Africa and the challenges of coming to accept oneself without the validation of one’s culture.

Dancing Lessons contains some downright hilarious scenes, as when a Rastafarian cabbie takes Gertrude on a wild taxi ride through Kingston. But for the most part Senior eschews the standard Jamaican laughs. Omitted as well are the bevy of “strong” maternal presences that bound back from misfortune and endure like Mother Earth. Senior replaces those idealistic icons with historically damaged women whose absent mothers and distant fathers prevent them from properly growing up.

An earlier version of this review appeared in Literary Review of Canada.