Hilary Mantel On The Giant, O’Brien and the Political Imagination

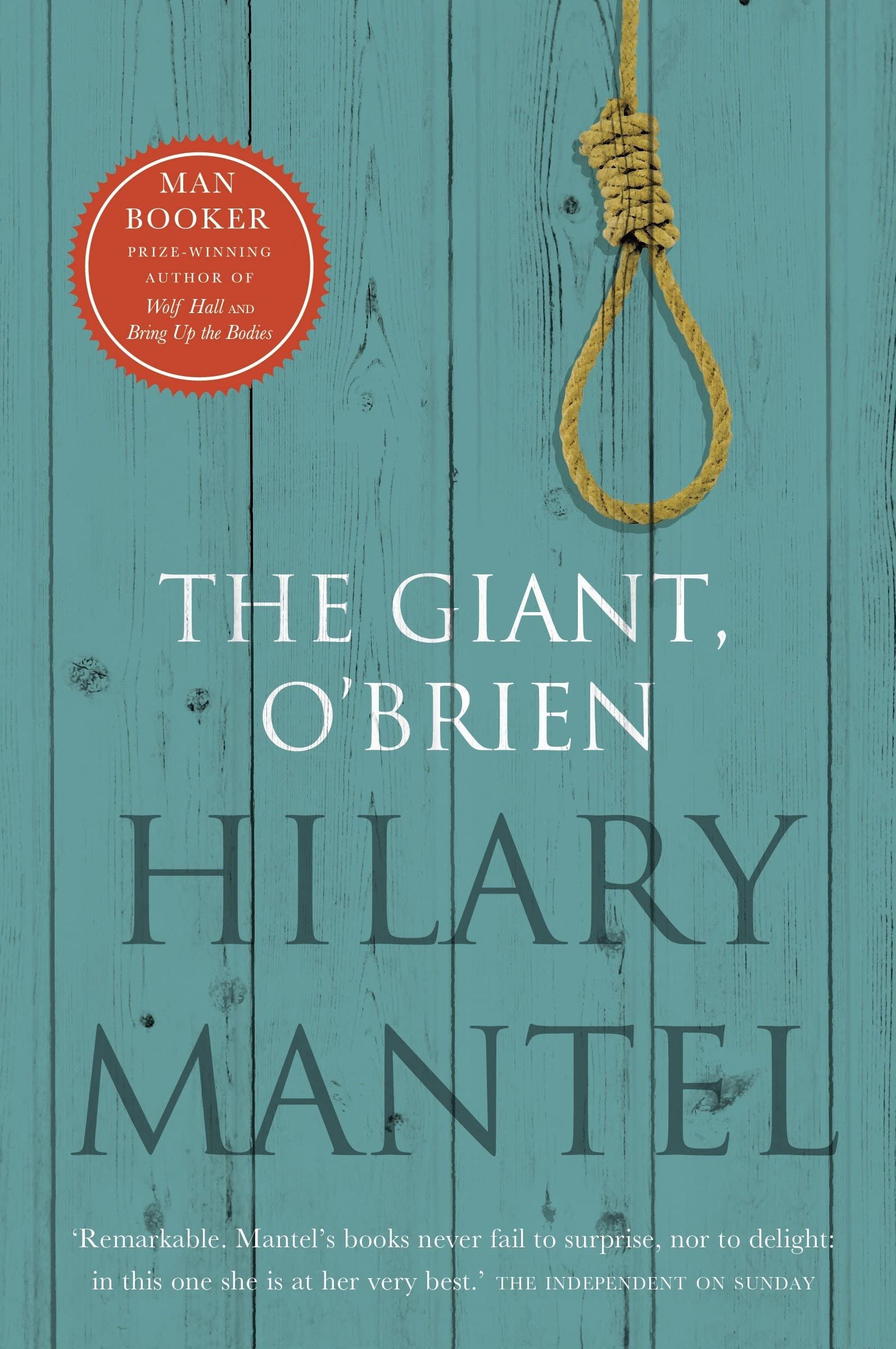

One of Britain’s greatest contemporary authors, Dame Hilary Mantel, has passed away at the age of 70. She is remembered now primarily for her Cromwell Trilogy - Wolf Hall, Bring Up The Bodies and The Mirror and the Light -that earned her two Booker prizes and was the subject of a BBC series and several stage plays. The Cromwell series, however, barely scrapes the surface of Mantel’s vast accomplishments, among them the novels A Place of Greater Safety, and also, The Giant O’Brien which I interviewed her about in 1999 for The National Post. The grimmest of fairy tales, The Giant O’Brien is based on the real-life figure of Charles Byrne who stood more than 8ft tall and involves the macabre real-life surgeon, John Hunter, who eagerly anticipates the giant’s death in order to collect and study his bones. Below is my interview with the late Hilary Mantel in which we talk about the impact on her imagination of Shakespeare, fairy tales and growing up Irish Catholic.

Hilary Mantel

On The Giant, O’Brien and the Political Imagination

By

Donna Bailey Nurse

Hilary Mantel

When Hilary Mantel is ready to get down to work, she leaves her comfortable home in a suburb outside London, England, and travels to Norfolk in the Northeast, to a two-room, red brick cottage near the village square. In Norfolk, it is difficult to find distractions.

Mantel might putter about the shops on the town's quaint main street or go for a walk along some lightly wooded footpaths. But she soon returns indoors, with all the time in the world to indulge in her favourite techniques for stimulating the imagination. Such as the one passed along by her friend, author Lesley Glaister.

"You must close your eyes and concentrate," explains Mantel, in Toronto to promote her latest novel The Giant ,O'Brien. "And then draw your attention from the outside of the building, to the inside of the building, into the room, and into your own body. You must create a mental space, and in that space, place a chair. And then you wait to see who comes to sit in it."

"That was how I first saw The Giant, O'Brien," she says, referring to her novel's Brobdingnagian protagonist.

"When he walked into the room, he leaned down and tested the chair. And I thought `Well, he'll always have to do that.' And so I knew a real thing about him."

Mantel is perhaps best known for her sweeping, fictionalized account of the French Revolution, A Place of Greater Safety, for which she won the Sunday Express Book of the Year Award in 1992. And also for her novel Eight Months On Ghazzah Street (1988), a chilling tale of adultery, intrigue and murder set in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where Mantel once lived. Critics laud her formidable intellect, her mordant wit, and her mercurial sensibility, which, according to one American reviewer, allows Mantel to "completely reinvent herself from book to book."

Mantel, who is of Irish-Catholic descent, is something of a modern-day Jonathan Swift. She is preoccupied with tortured political relations, particularly relations between England and Ireland. Like Swift, Mantel often employs a savage satire to draw attention to political ineptitude and social injustice. Every Day Is Mother's Day (1985) and Vacant Possession (1986) were fiendish send- offs of the British welfare system. The Giant, O'Brien recalls Swift's Gulliver's Travels in its use of the human form as a metaphor for the body politic.

The hero of Mantel's eighth novel is derived from an actual historical figure: The 18th-century Irishman Charles Byrne, who stood nearly eight feet tall. Historians believe Byrne may have been developmentally handicapped. But Mantel's O'Brien possesses the great oral gifts of the giants of Irish folklore, revered in Irish mythology for their storytelling skills. Like the original, Charles O'Brien abandons an Ireland racked by cyclical famine and sets sail for England, hoping to parlay his unnatural height into a fortune.

For a time, Londoners flock to the venue where he has placed himself on display, eager to catch a glimpse of this human colossus. But O'Brien's notoriety lasts just one season, and his health begins to fail. The giant and his followers wind up sharing quarters with other desperate Irish and assorted freaks in London's oozing, putrid streets.

Enter John Hunter, (also based on an historical figure) the famous surgeon and anatomist, with his unfettered appetite for knowledge about the human body. He requires an endless supply of cadavers on which to conduct experiments and dissections. Hunter remains in the background for much of the novel. He hovers like a vulture, waiting for O'Brien to die so he can add his behemoth bones to his collection of unusual specimens. The giant's bones hang still in the Hunterian Museum in London's Royal College of Surgeons.

The story reads like an allegory or a macabre fairy tale. Mantel contrasts two cultures: Irish and English, and two types of knowledge, science, and poetry. She divides the world into two distinct periods: future and past. In The Giant O'Brien the present is fleeting, elusive.

Mantel looks a bit like a fairy-tale character herself. She has translucent, pale skin. And baby fine blond hair. Her great blue eyes put me in mind of lake waters -- reflective surfaces suggestive of great depth. Meeting with her in Toronto, she admits that The Giant, O'Brien is not quite the story she set out to write.

She meant for O'Brien to play an incidental role in a novel about Hunter's life. But all that changed when she came across a book published in 1924 called The Hidden Ireland.

"It's an obscure and strange little book in many ways," says Mantel in precise, birdlike tones. "It dealt with Irish poetry at the end of the 18th century, in the time of the giant, when the native tradition and its secrets were on their last legs. Irish poetry was a very specific art with very specific rules. In the golden ages of literature, it was said to take a 12-year training to become a poet. But this was long gone by the giant's day.

"No other book has infused me with such a sense of mourning. And I couldn't think what I was mourning. Because the poems in the book don't translate very well; they don't mean much in English. I couldn't think why I felt sad to my roots. And then I decided it was to do with the loss of [the Irish] language. Something really profound had gone missing from my life."

Derbyshire

Born in 1952, Hilary Mantel grew up in Derbyshire in the village of Hadfield, beneath the moors. It was a bleak, insular, cotton- spinning hamlet, inhabited by successive waves of Irish immigrants who had come to work in the mills. Mantel's own family had resided in Hadfield for generations. She lived with her mother (she has little recollection of her father) in her grandmother's home, which was set in a row of workers' cottages. Each had two rooms up and two rooms down, a coal shed out back and an outside lavatory. They shared a long, communal yard.

"When you were growing up in that town, one of the first things you knew about people, when you were five years old or so, is whether they were Protestant or Catholic. I won't say there was any ill feeling . . . but there was consciousness. I would play with a little girl from down the yard who was a Protestant. She was like me in every little respect. Same little frock, same little bonnet, just three months older than me. Except she was a Protestant, which meant she would burn in hell for all eternity unless she saw what a mistake she was making. What a thought when you're playing skipping games!"

Mantel grew up ensconced in a vast extended family. And what she chiefly remembers is: Talk. "My grandmother and her eldest sister lived next door to each other. My abiding image -- from the time I was two and three and four years old -- is of my aunts on either side of the fireplace. They'd be sitting and talking -- people, people, stories, stories -- punctuated with these kind of refrains.

`I wish I were 10 years younger' and from my great aunt, `We were born too soon, Kitty, we were born too soon.' Everyone had a story attached to him or her."

At school, teachers considered Mantel somewhat dull, perhaps because she was generally very quiet. But she loved stories, especially tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table.

She dreamed of fantastic giants, ghostly castles, ladies of the lake and dragons. When she did speak, it was often to utter a romantic, antedated phrase, such as "Unhand me you swine!"

At the age of eight, she encountered Shakespeare in a discarded school text. It was the passage from Julius Caesar in which Anthony shows Caesar's body to the mob and turns the crowd against the conspirators. Says Mantel, "Everything I've been writing about ever since -- powerplays, assassinations, political struggles, mobs, how to turn mobs -- everything is in that scene."

Indeed, Mantel is a real political animal and for a time had a weekly column in a London newspaper. But the work that benefited most from her passion was undoubtedly A Place of Greater Safety, her chronicle of the French Revolution, experienced primarily through the figures of Desmoulins, Robespierre, and Danton. Mantel's face still beams like a proud parent when she speaks about the book. It is clearly her favourite, although it came close to never being published.

After graduating from the London School of Economics, and marrying her high school sweetheart, Mantel worked as a social worker in a geriatrics' ward. She eventually quit that job, however, to take a less psychologically taxing position as a shop clerk. She needed to focus her energy on her book. Mantel spent most of her 20s researching and writing. She built an extensive card file that contained an entry for every day of the revolution. She finally finished the second draft of the book in Botswana in 1977, where her geologist husband had travelled to work.

But three things happened that caused her to set the novel aside: the publisher who had expressed interest decided he was no longer interested; on leave in England, she lost her only copy (the original was in Botswana 7000 miles away); and she suddenly became gravely ill.

Mantel refers to these events as creating a fault-line in her life. She put the novel away. Out of sight, out of mind. When she was ready to work again, she decided to attempt something less ambitious. "I will write something short," she thought, "something conventional, something contemporary that publishers will find easier to come to terms with as a product from a still fairly youngish woman whom nobody ever heard of. And in this way I will surprise them."

Which she did in due time, garnering a steady increase in critical acclaim from the mid-'80s onward. A Place of Greater Safety was finally published as her fifth novel.

Mantel describes The Giant O'Brien as a bookend to her story of the French Revolution. They explore many of same political themes, such as what it means to be human, the idea of the body politic and the condition of exile.

"If you have the consciousness of a more settled people," says Mantel, "the condition of exile is an idea you might pour scorn on.

But suddenly, when I hit middle-life, it became important for me to get a sense of these things.

"When I read that book, The Hidden Ireland, this feeling of exile and loss and displacement grew in me rapidly. A void opened and I had to look for some voices to fill it."

With The Giant, O'Brien, Mantel again locates her muse in 18th- century politics. The story is set largely in England and based nominally upon two historical figures, the giant Irishman Charles Byrne, and John Hunter, a Scottish anatomist. Mantel calls her titan Charles O'Brien and it is 1782 when he decides to exchange a life of poetry in Ireland for a career in London as the tallest man in the world.

The Giant, O'Brien is an elegy for Ireland's disappearing culture. But it is also a horror story. The ghoulishness that surrounds Hunter comes not so much from his preoccupation with the human form as from his intemperance and soullessness. In his desire for scientific advancement, Hunter considers only the substance of things: Dead bodies are mere slabs of meat and the giant, a freakish collection of bones. Hunter attaches no value to the ancient bardic traditions O'Brien's body housed. For Mantel, England is to Ireland as Hunter is to the giant: Both annex a foreign property without concern for the spirit within. They fail to honour the relationship between content and form.

This piece previously appeared two decades ago in the National Post for books editor Noah Richler.