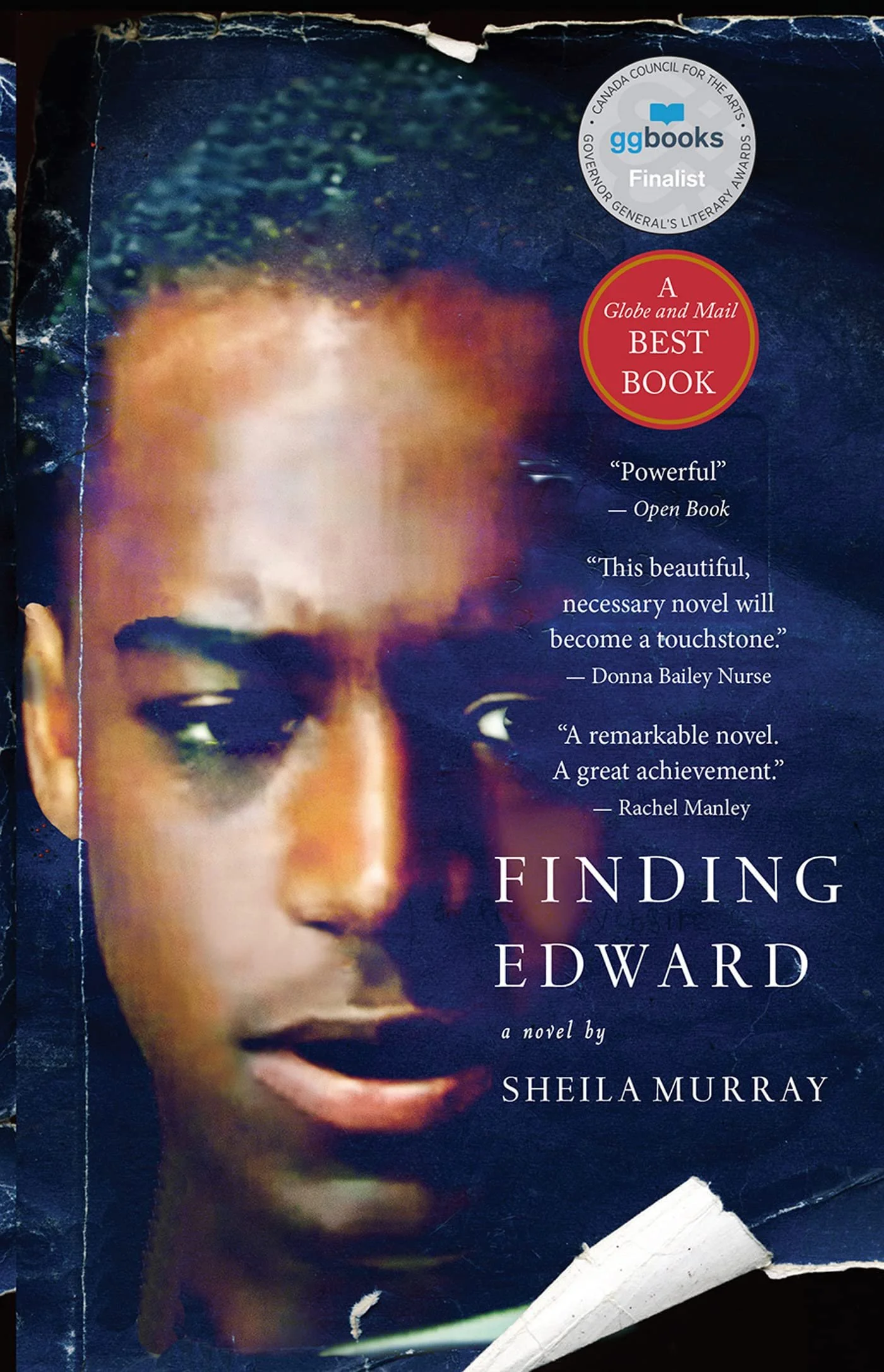

A Review of Finding Edward

Sheila Murray, author of the remarkable and moving debut Finding Edward, exhibits a paradoxical ability to articulate the unwieldy dimensions of real life while maintaining a refined and nuanced style. Amazing to me is the technical dexterity with which she constructs the marvellous complexity of her story.

Her protagonist, Cyril Rowntree, is the son of a Black mother and an absent white father who grows up in a closeknit Jamaican village. After the death of his beloved mother, Cyril makes the dramatic move to Canada. With a small legacy from his late benefactor, Nelson, a professor of Black Studies, he plans to continue his education. Nelson, his mother’s employer, had acted as a surrogate grandfather, introducing Cyril to poetry, and taking him on trips across the island. In Toronto, though, Cyril is desperately alone, though that feeling begins to wane as he becomes obsessed with a Depression-era mystery involving a bi-racial boy abandoned by his white mother.

In Finding Edward three central characters possess mixed-race heritage: Cyril; the mysterious Edward; and Pat, the mentally ill Indigenous woman who introduces Cyril to Edward’s story. Although Pat identifies as Ojibwe, her mother is white. Cyril’s white father abandoned the family and returned to the U.K. when he was small. Cyril still harbours painful feelings of rejection and loss:

“What he wanted to know was: How do you father a child and then move 5,000 miles away? If his dad were here, would his life be different? Would his dad take him to the places he wanted to see – Niagara Falls, the Rocky Mountains? Would his dad hold him in a bear hug and tell him that everything’s going to be okay, that there’s a future for him… in this city?”

Old letters written by Edward’s white mother disclose that she became pregnant after a passionate affair with a Black man. Although, she longed to keep her baby, she lacked the financial, familial, and psychological resources necessary to raising her illegitimate Black child in 1920s Toronto. In short, the stigma was too great.

Bi-racial heritage is a prevalent theme in Black Canadian literature, even for Black writers who are not mixed-race. All Black Canadians – indeed, descendants of Africans around the world – are inescapably shaped by a history of enslavement and colonialism and the hegemony of European culture for which the degradation of African peoples has served as foundation. Consequently, Black Canadians are partly the product of the very culture that rejects them.

That Black people are spurned - often treated by white culture as illegitimate offspring - is the complicated idea Murray brilliantly embodies through her protagonists and their estranged white parents. Born in the U.K. in 1955 to a Black Jamaican father and a white British mother, Murray eloquently communicates such profound and personal ideas.

Just as she acknowledges the furtive family ties between African and European cultures, Murray also affirms the Black lives of socially invisible men like Cyril and Edward. Over the course of the action, she brings their stories into the light. Black and forsaken, barely old enough to string words together, Edward is given over to Toronto’s Depression poorhouse. In freezing freight-yards, he joins other destitute boys gathering excess coal that falls from traveling boxcars. A chronicle of ups, but mostly downs, his is a perpetual battle against indigence. His long, peripatetic life journeys across Canada through a vibrant, little-known Black history.

Edward’s tale subtly mirrors Cyril. And in slowly unearthing it, Cyril broadens his understanding of contemporary Canada and the wider world and begins to carve out a place for himself. In one way, Cyril’s story is extremely familiar to hundreds of thousands of Caribbean- Canadians, including myself. My father arrived in Canada from Jamaica as a young man and like Cyril enrolled in university. With my mother- he began to construct a new life. Over the decades, I have read many excellent novels that vividly delineate the experience of Caribbean immigrants in Canada. And yet never have I so thoroughly comprehended the fear, courage, loneliness, hope, excitement, tenacity, and intellectual creativity involved in transporting one’s life from that world to this.

One thing that feels particularly fresh just now is Murray’s tender portrait of the Jamaica Cyril leaves behind. Positive depictions of Jamaica are rare among the contemporary voices that are making up for lost time with their horror stories of entrenched poverty, sexual oppression, colourism, and deadly homophobia. Although Murray does take care to underscore the harsh facets of the Jamaican condition, her warm-hearted rendering of the island is equally true: a country of staggering beauty, familial affection, faith, generosity, and “One Love.”

Sheila Murray

While rarely found in Canadian books and newspapers, Cyril is the kind of intelligent, upright young man Jamaica regularly turns out. In Toronto, he becomes a walker in the city, and we literally follow in his footsteps as he takes long exploratory walks around the west-end to ease his loneliness and to avoid the unpleasant extended family with which he originally resides. We are privileged to follow his train of thoughts which are of such emotional verisimilitude they might be our own.

As with any Black man who innocently takes up space, there is the evil and inevitable encounter with police. At the same time, Cyril finds friends in the most unexpected places. For example, the young Black woman who engages him in the street with her candid views on colonialism and Canadian-style racism. At Ryerson University, where he is accepted, he builds meaningful relationships, explores his racial identity, and receives guidance and support in his search for Edward.

This is a moving and essential novel; and not incidentally, one of the most complex and beautiful disquisitions on Toronto I have ever read. For example, this scene in which Cyril travels by streetcar to visit the downtown core for the very first time:

“The trip to the city took a lot of his concentration, especially the streetcar. He dropped his paper transfer just as the trolley arrived but managed to catch it in an updraft on the street. He retrieved it just before the doors closed. As Cyril squeezed into a standing space between two middle-aged men, the sun cut free from the clouds, transforming the day, shining winter brilliance over the buildings and glass storefronts, people, cars, and bicycles. Everything glowed and sparkled. The city was radiant.”

Donna interviews Sheila Murray about her unforgettable novel Finding Edward for the Vancouver Public Library on Thursday, February 16, 12 pm PST/3 pm EST.