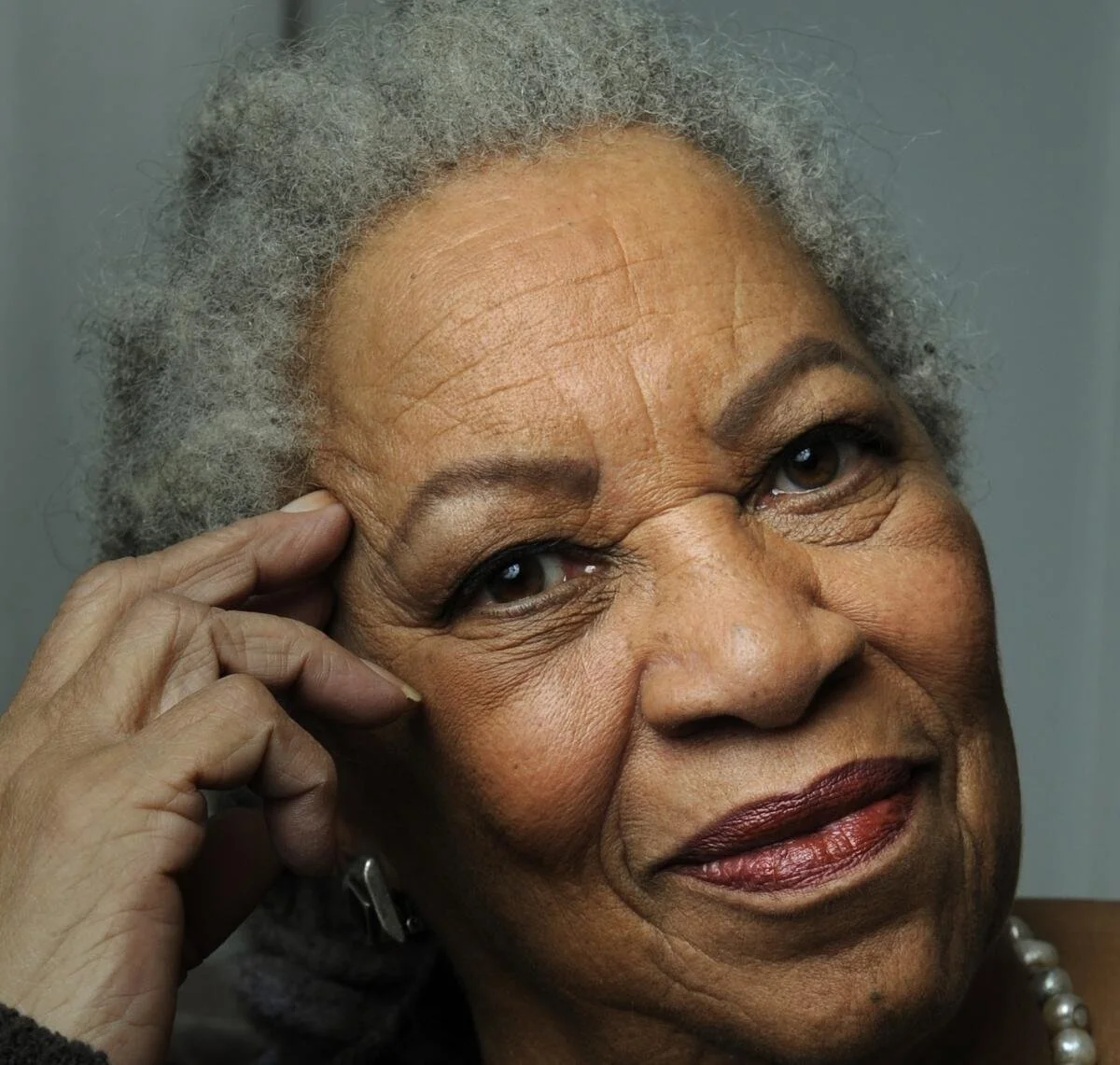

Home by Toni Morrison

As I was reading Home, Toni Morrison’s latest novel, two works came to mind. The first is Marilynne Robinson’s novel of the same name; the second is a popular poem by Gwendolyn Brooks. Like Robinson’s novel, a central character of Morrison’s Home is America in the 1950s, while the others are a brother and sister who reunite after some years. Like Robinson, Morrison explores the challenges of confronting an unsatisfactory past. Both books deal with religion and race — American literature’s two great themes.

But the America Morrison’s Black characters inhabit is a far cry from the picket-fence milieu of Robinson’s white ones — which is what got me thinking about Brooks’ poem. “We Real Cool” describes a group of African-American boys who skip school one day to play pool. The poem is not so much about “what they do” as it is about “how they do.” Its syncopated rhythm breaks up time; its meanings resolve on the offbeat, its famous line — “We jazz June”— dismisses, disrupts, and complicates conventional associations with that loveliest month of the year. Likewise, with Home, Morrison jazzes our idealistic image of 1950s America. She scratches that sepia-toned album of postwar prosperity, small-town security, domestic bliss and the nuclear family. Morrison gives us Home: The Remix.

Her hero is Frank Money, a 24-year-old veteran of the Korean War. It has been a year since Frank returned to his base at Fort Lawton, but he has yet to make it home to Georgia. For one thing, he met Lily and fell in love; for another, he is suffering from post-traumatic stress. He witnessed his friends’ death on the battlefield. Another secret horror excites hallucinations and frenzy.

Our meeting with Frank is a head-on collision: As the novel begins, he is barrelling out of a mental hospital and racing barefoot through the frigid night. He takes refuge at Mount Zion, where Pastor Locke offers food, shelter, some galoshes and $17. The cash will take Frank as far as Chicago.

From there, he will board a train to Atlanta, where his younger sister Cee lies near death. Cee is Frank’s one true thing. He felt protective of her even before she was born; 20 years ago, whites ran his family and their neighbours off their Alabama land. They left everything but Cee, who was in her mother’s womb.

The family moves in with their grandparents in Lotus, Ga. It is a miserable situation. Their parents slave day and night to be able to afford their own place; their selfish step-grandmother resents having to share her home. When war breaks out, Frank flees Lotus for the thrill of the battlefield. Lonely, Cee marries a scoundrel who abandons her in Atlanta.

The American dream of home ownership proves elusive even for Morrison’s comfortable, northern characters. Take Frank’s girlfriend, for instance. Lily works as a make-up artist for a small theatre troupe, eventually saving enough to buy her own home. She spies an attractive neighbourhood, but the residents will not sell to Blacks. Hurt and frustration eventually sour her love for Frank.

Georgia, USA (photo by Nils Leonhardt)

Morrison’s indictment of mid-century America moves beyond race. Lily’s theatre shuts down after staging a play by Albert Maltz, a screenwriter and one of the Hollywood Ten — writers and filmmakers who were blacklisted and imprisoned for defying the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Peacetime is hardly less deadly than war. Klansmen bludgeon to death a Black man who refuses to leave his home; police shoot a Black child in the arm, leaving him handicapped; and a distinguished doctor performs grotesque experiments on the wombs of African-American women. This violence is simply the difficult truth, and it has been Morrison’s task to figure out how to tell it. In Beloved, she distracts readers with a ghost. In Home, she considers the male instinct for violence, weighing an individual wicked act against a culture’s collective, institutionalized evil.

Always, she relies on her people’s oral tradition: Verbal games and music: jazz, blues, gospel’s call and response. A man from everywhere, who rides the rails and pines for lost love, Frank Money embodies the blues.

Here is a scene from the Chicago diner where Frank stops en route to Georgia.

“Where you from Frank?”

“Aw, man. Korea, Kentucky, San Diego, Seattle, Georgia. Name it I’m from it.”

Jazz player (photo by Konstantin Aal)

“You looking to be from here too?”

“No. I’m headed on back to Georgia.”

“Georgia?” the waitress shouted. “I got people in Macon. No good memories about that place. We hid in an abandoned house for half a year.”

“Hid from what? White sheets?”

“Naw. The rent man.”

“Same thing.”

“Why him?”

“Oh please. It was 1938?”

Up and down the counter there was laughter, loud and knowing.

This superb display of “call and response” demonstrates how shaping pain and sharing it operates for Blacks as a means of transcendence. Elsewhere, winding sentences contain whole stories of wandering sound that emulate the jazz solo.

I do not think Morrison always resolves this tension between words and music. And I don’t think she even wants to. We come upon phrases that seem wilful in their dissonance — horns blown deliberately out of tune.

At the same time, Morrison loves language. She is a master of the metonym; she constantly plays with form. Home is a horror story, a ghost story, a fairy story and also an allegory: Frank Money represents what it means to be a Black man in a capitalist society. Pastor Locke is named for the philosopher who profoundly influenced social and economic thought. With Pastor Locke’s church, Mount Zion, Morrison draws an analogy between the Hebrews wandering in the wilderness and African Americans seeking their true home. Not for the first time, she points us due South.

An earlier version of this review appeared in the National Post.