The Window Seat: Notes from a Life in Motion. An Interview with Aminatta Forna (Part 1)

The Window Seat: Notes from a Life in Motion

An Interview with Aminatta Forna

PART 1

I defy anyone to read a book by Aminatta Forna and remain unchanged. It’s not just because of the sweeping intelligence that informs her consciousness of the interconnectedness of living things; it’s the visceral impact of her writing that physically alters us, that embeds us in her fictional landscapes. Her words exert a gravitational pull. To read one of her novels is to be trapped inside a dream: you are powerless to hurry the experience or slow it down. What’s more, her characters follow you right off the page and into your own life.

Aminatta Forna was born in Glasgow in 1964 to a Scottish mother and a Sierra Leonian father. Her first book, The Devil That Danced on the Water (2002), tells the story of her father, Mohamed Forna, a medical doctor and politician assassinated by the Sierra Leone government in 1975. The first part of her memoir carries us back to her childhood where Forna is obsessed with books and animals and bemused by the political drama swirling about her father. In part two, Forna now a BBC journalist, returns to Sierra Leone to track down the individuals who betrayed her father.

Forna has published several novels including Ancestor Stones (2006) and The Memory of Love (2010) which won the Commonwealth Writers Prize. Her latest book The Window Seat: Notes from a Life in Motion (Grove) is a riveting collection of personal essays set around the world, exploring politics, identity, the western gaze, and human co-existence with wildlife. Indeed, animals, especially dogs, remain her greatest passion. Says Forna, “Animals may be dangerous, or they may be harmless, but you know where you stand with them.”

In the essay Obama and the Renaissance Generation, Forna draws parallels between her father’s life and that of President Obama’s father, both of whom came of age at a particular moment in African history. Here is where our conversation begins:

DBN: What moved you to tell the story of Obama’s history which many people undoubtedly thought they already knew?

AF: I was moved to tell it because it chimed with my own. I remember when Obama was elected, reading about his history, and thinking, “Oh, good! Now I don’t have to explain my background. I can say, it’s like Obama’s.” I did a radio program around that time - two radio programs actually: One was a written monologue by various writers at the time of his inauguration. I developed it into a radio programme called The Renaissance Generation. I was really prompted to write the essay because I had a sense of pride that Obama had been in power for as long as he had. Even so, many Americans hadn’t grasped the significance of his background.

DBN: Part of what I love about that essay is the way it reminds me of the awesome trajectory of our parents’ lives. Yours more so than mine, perhaps - but I still think about my father growing up in Jamaica, rising before 4 a.m. to walk to the family plot he worked with his siblings before heading off to his one room school. And then coming to a very foreign, hostile land to attend university. Despite obstacles they faced, our parents frequently excelled.

AF: My stepfather worked for the United Nations. He rose to be an assistant secretary-general. But he started out on a farm outside Christchurch, New Zealand, riding horses bareback. My mother grew up working-class in a provincial town in Aberdeen. My father had a reasonably aristocratic background as his father was a regent chief and his mother had been what would be translated as a princess. She was considered royal and so was her father. She had this extraordinary history: she was enslaved and freed.

They still grew up in a small village and hinterland without access to Western education. (And I am careful to say Western education because they were educated). But they were all born when the world was at a particular point of change and so you could go out and do these amazing things. My stepfather joined the United Nations soon after the war when it was just an idea and spent his entire career in it. And my mother met my father when women could just about see their lives beyond the script that was laid out for them. My father, similarly, was born on the cusp of history.

DBN: I know history gave them all the opportunity. But certainly, your father as a Black man and an African man, faced a deeply unfamiliar and often hostile environment. It must have been more challenging.

AF: Much more. But he didn’t expect his life to be easy. I think that’s a big clue. I was talking to Tim Phillips who runs a peace-building organization in the United States called Beyond Conflict and they’ve been doing a lot of work on identity because of the “so-called” culture wars. We were having a Zoom chat about identity, and I said I get this (preoccupation with identity) - but I don’t get it. I have always grown up knowing that I have multiple identities. I’ve grown up knowing they overlap; I’ve grown up knowing they are changeable. I’ve grown up knowing it depends a bit on how you simplify yourself and about how people see you. And it’s mutable. And so, I’m somewhat baffled by the reduction to the binary: You’re either this or you’re that. Or you’re this or you’re that. Phillips says the research shows that when there is an assault on your perceived identity, or anything that might change your status, people - apparently - feel personally attacked.

DBN: You say “apparently” - so not you then. You don’t feel attacked.

AFN: No, I don’t. I think that’s up to you. But we’re talking about what’s happening in America. The feeling some people have that their status is under threat. The one element most of the research doesn’t take into account, but which is becoming evident, is confidence.

DBN: Confidence? What do you mean, exactly?

AFN: I’ve often thought that when people really need an off-the-peg identity it must speak to a lack of confidence. In other words, you need lots of cohorts and you need a group around you. You need all of that to feel safe in this world. But if you already know that the world is unsafe. And you already know that you have to navigate your way through it, and you already know life is going to be shit, sometimes you go forward with a different way of seeing, a different way of thinking about yourself. To bring it back to my parents: What they had was this immense confidence. Either they were given it, they were born with it, or they were taught it. One way or the other they went forth with that confidence.

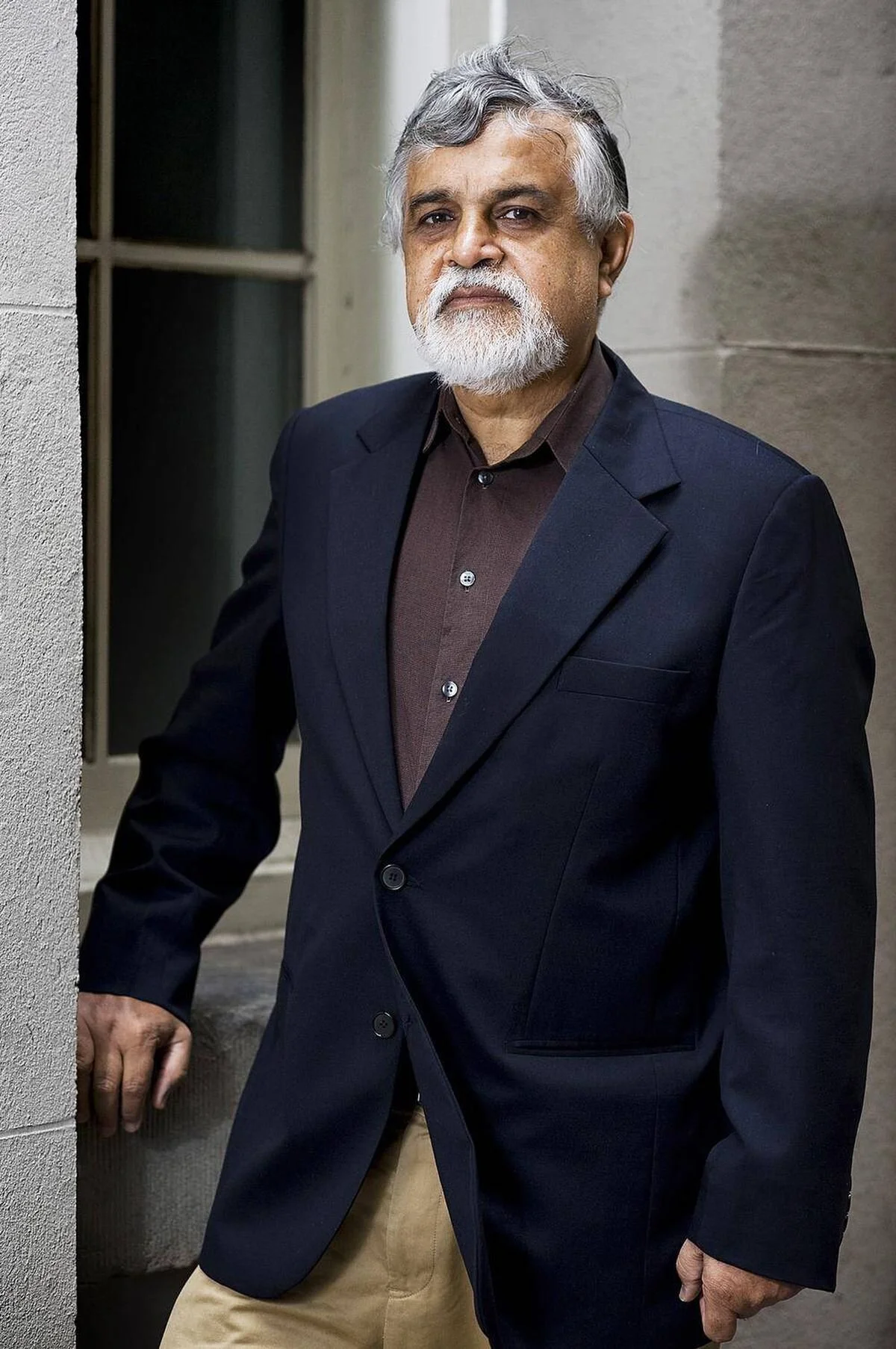

Aminatta Forna, Daphna Rabinovitch and Donna Nurse at the 2019 Scotiabank Giller Prize jury dinner

DBN: Wow. That’s interesting. But what about your ability to reconcile your various identities? I ask because this is something I struggle with: I’m Black, I’m female, I’m Canadian, I’m Jamaican and I often feel my identities are at war with one another. Certainly, they are tussling. Do you feel that way?

AF: Well, I feel like there are people who would like to make me feel like that.

DBN: No. I really want to know if you feel that way or not.

AF: I don’t feel it. But I know I am under pressure to feel it. And I am under pressure to feel it because I am so often asked to prove my identity. And I have consistently - since I became an adult and aware of this game - declined to play it.

DBN: What do you mean people want you to prove your identity? And what do you mean when you say it’s a game?

AF: I mean, they want you to prove how British you are; prove how Sierra Leonian you are. In Sierra Leone my skin is lighter, and my accent is British: Well, then, are you really Sierra Leonian? Of course, this is unless somebody wants something from me. Then I’m very, very Sierra Leonian. It’s the same thing with Scotland: Well, how Scottish are you? Well, your name isn’t Scottish; well, your skin is too dark; well, you speak with an English accent. How Scottish are you?

And I just declined to play that game a long time ago because I realized it was a game. Since you and I spoke last, the Euro 2020 football match was played, and we saw what happened right away. Those Black men were all English until they missed their penalties and then people started going against them. Of course, some people stood up for them, but many others behaved appallingly. You see that! It’s a game being played with you. My position is I refuse to play that game. I am two and three and five and ten things at the same time. Also, so are you and you and you and you. You might pass as Scottish, but your ancestors were probably Vikings like mine. You might pass as Sierra Leonian, but your ancestors may have been Malian like mine. We are none of us one thing.

DBN: Another reason these essays are so absorbing is that you appear in the action as a character. I wonder if you are speaking to the Western reader who also exists in these stories but doesn’t seem to realize it. Is that something you think about?

AF: Yes, I do. One of the things that plays a lot in my writing is reversal of the gaze. We’ve read for several hundred years how you see those in my world as “the other.” Let’s have a look at how we see you. So, when I tell the man in the piece Timbuktu that Westerners consider his city the farthest place on earth, he bursts out laughing. To him Timbuktu has history. It had several universities in the 14th century. It was part of the Malian Empire and part of the Songhai Empire - huge empires that lasted hundreds of years. They traded massive amounts of gold and silver and slaves (prisoners of war). How could a little island like Britain - with an empire that barely lasted 100 years - even compare.

Songhai Empire

I made several films in Mali. And I remember in the first one I had to speak to a Songhai chief – the Songhai Empire was huge and lasted a very long time. I interviewed him, and I mentioned the French Empire and he just scoffed and laughed, “The French! They didn’t even last a hundred years!” So, I do think that once you start looking at anything close to deep time, or medium time; once you start looking at 500 years, 1,000 years, you are looking at different centres that have risen and fallen. And I think it would be wise for all of us to be able to acknowledge that, and see where we stand, including people who are currently at the centre.

DBN: I want to return to the Obama essay for just one moment. While that piece begins with a discussion of the fathers - your father and Obama’s father, it winds up focused on the two white mothers. The Renaissance essay, and the one called Hame, leave me with a much stronger impression of your mother than your memoir did. Until now readers have been more fixated upon your father.

AF: Well, two things: Readers actually were quite fixated on my mother when I wrote my memoir. Sometimes it aggravated me. Hang on a minute! I am writing about a man who gave his life for something, and you are more interested in the woman he married because she looks like you?! That irritated and troubled me. But I think that in general where the focus has been on the two men- (Obama Sr. and my father)- it is probably because they are men and men’s lives are more visible than women’s lives. They’ve always been able to play a larger role in the world; but also because their countries - my father’s country and Obama’s father’s country – went through the ruptures of independence. Their countries were at the centre of something – of colonialism and post-colonialism. Whereas at that time Britain was a declining power, and America seemed to be in a very safe, secure position. The women didn’t seem to be at the nexus of history the way that the men did.

Obama wrote a bit more about his mother in his second memoir. It was really when I read that book and some biographies about him, that I saw the connection between his mother and my mother. These were women who were just not prepared to be so small, to live small lives. And one of the ways in which that manifested itself was by choosing partners from elsewhere. And that was probably a lot to do with the time: Marriage was a way in which you changed your life, much more for women then than it is for women now. Although, it still is for women much more than it is for men. In my cohort I’ve seen women marry men who change their lives, more than I’ve seen men marry women who change their lives.

So, I think it was very much a possibility to marry and change your life in that way. But then what is interesting is that when the relationship is over the women carry on, and the men go back to their country. My father went back to Sierra Leone. He was a man of the world. He travelled a great deal. He had an international career. But essentially, he was a Sierra Leonian. That was always home and that was what he was committed to. And Obama Sr. goes back to Kenya and doesn’t plan to leave again. Whereas the women - what do they do? They go off and lead these international lives. I wrote about my father for obvious reasons: He died when he shouldn’t have; our country went through decades of ruptures. But it seemed to me that this was the time to write about my mother. She had done something remarkable.

DBN: We witness your mother’s courage in the essay 1979 which is set in Tehran at the moment of revolution. At great risk to herself, your mother, Maureen, hides a group of people forced to flee for their lives. You dedicate The Window Seat to her. Do you feel you have gotten to know her better over the years?

Mohamed Forna and Maureen Campbell White

AF: I feel I know her better through writing about her. Both through the Obama essay and the Hame essay. I wanted to write Hame, about my mother’s family history, a long time ago. The editor of my book John Freeman was editor of Granta when we met, and I proposed to him two essays: The Last Vet and Hame. He loved The Last Vet, but said he couldn’t get his head around Hame. Time passed, and anyway my mother was working overseas, and I hadn’t figured out how to put the essay together. But when she retired and her travel became more for leisure and interest than for work, I thought, why don’t we go (to the Shetland Islands).This might give the essay the shape I’ve been looking for. And it’s really turned out to be one of the most popular in the collection.

DBN: Yes. I really love Hame; I loved the feeling that I was visiting the Shetland Islands with you, your mother and brother and learning the history alongside you. It’s a place I’ve never been before, not even in my imagination.

AF: My younger brother who I adore -who let me make clear is a white man. We talked a little bit on the trip about how we came from the same parent and yet we have this trajectory in the world that is defined by the way we look. His wife is Chinese, and he is sensitive to the fact that the women in his life don’t have the same advantages as he has; the same privileges as he has. I became a writer and a university professor. And he works for Apple! As somebody once said, “Of course he does!” But we’re both doing well. I love my life. I’m not complaining.

Aminatta Forna is the author of The Window Seat: Notes from a Life in Motion. This interview was conducted by Zoom on July 15, 2021. Part Two of our conversation will be published next week.