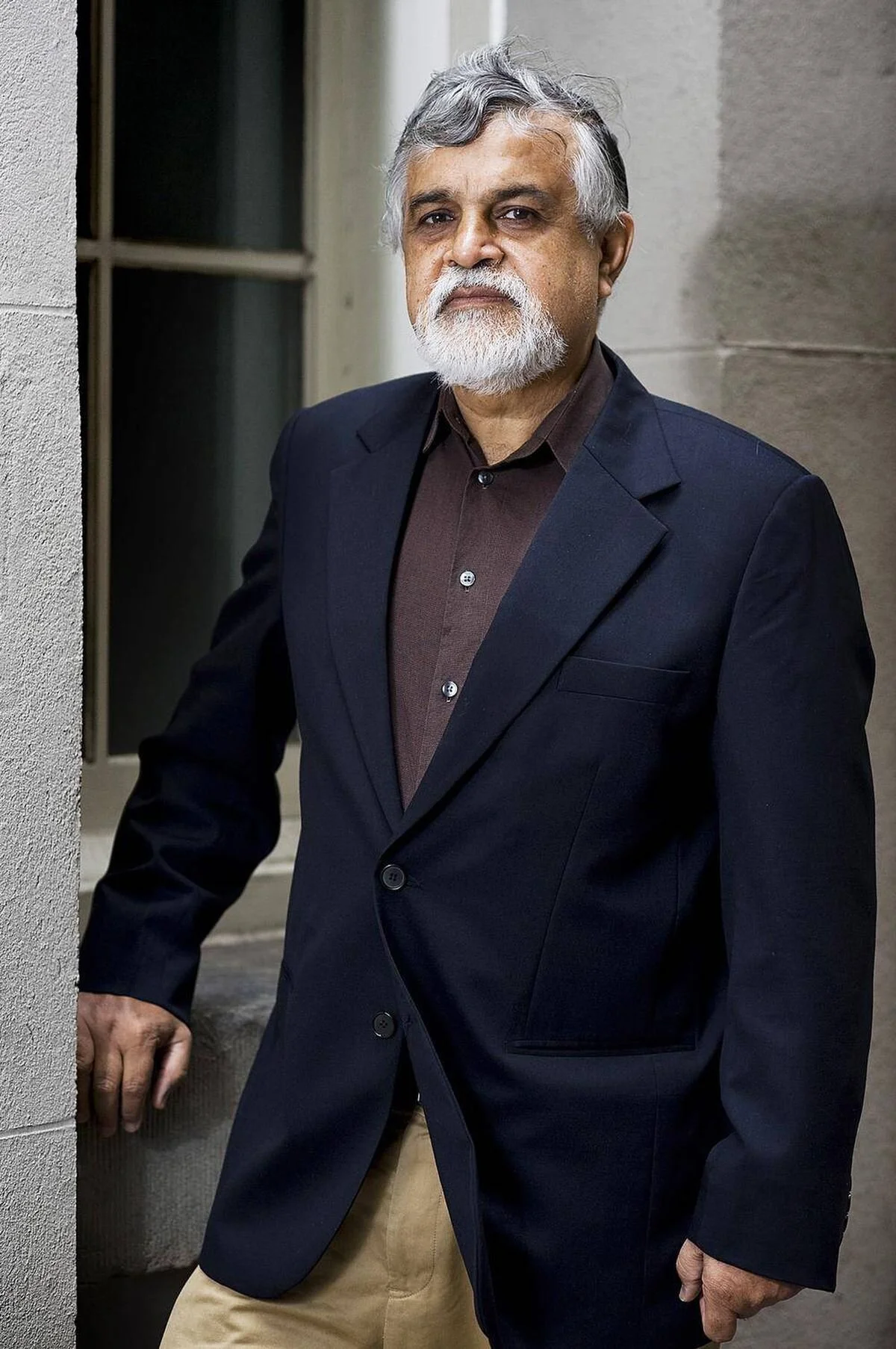

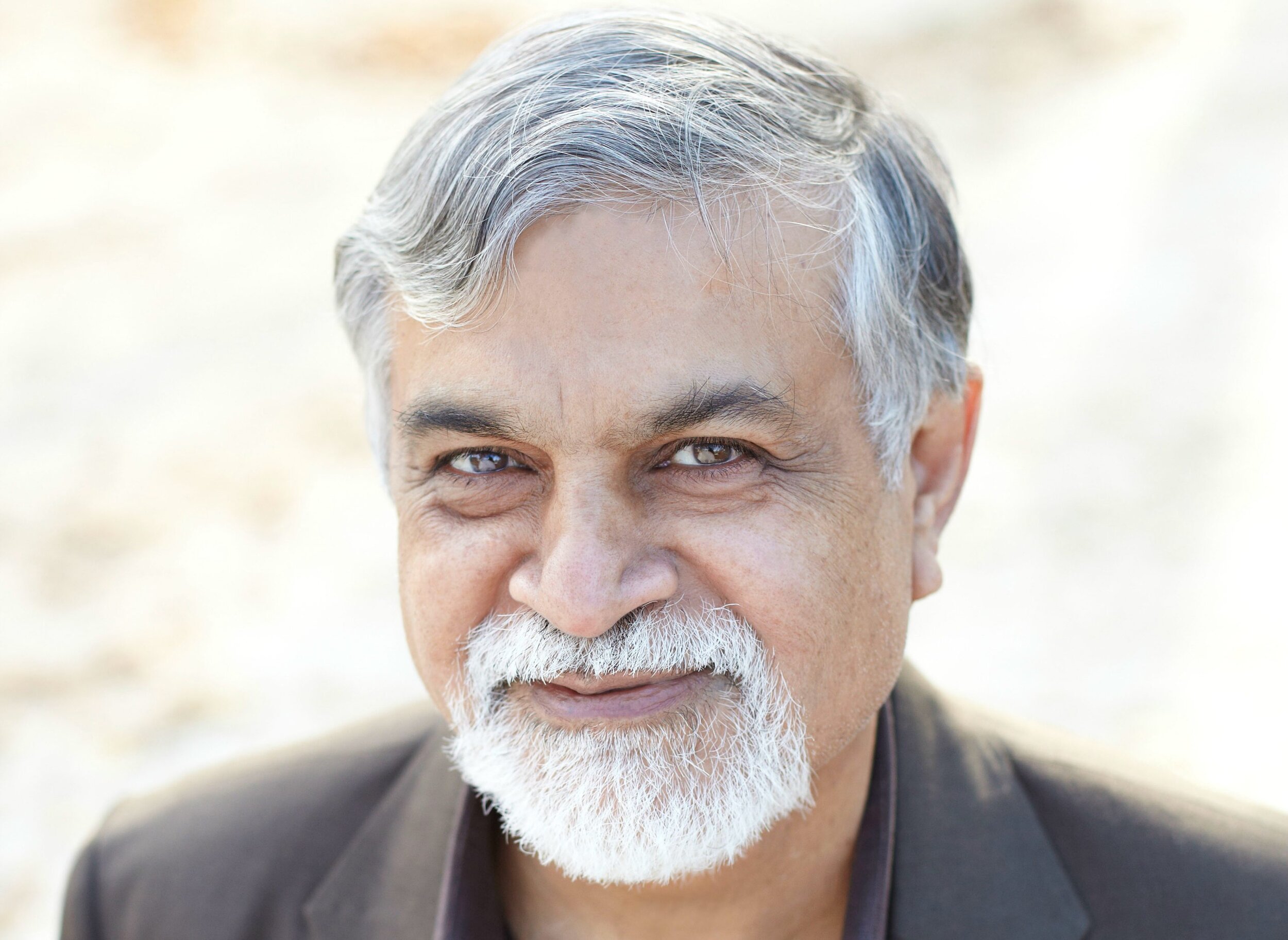

What You Are: A Candid Conversation with M.G. Vassanji (Part 2)

What You Are: A Candid Conversation with M.G. Vassanji

PART 2

DBN: Marriage comes up often in your work, but especially in the story The Sense of An Ending. What does marriage help you explore?

MGV: Family. Traditions. Relationships over time. Where does a relationship end up? And, also, the kinds of compromises that people make in real life when they decide to marry, a topic I also discussed in my novel A Delhi Obsession. In the Delhi tradition there is the arranged marriage – although now we have love matches as well. Marriage gives you a companionship you don’t have to struggle for. Otherwise, you are living an animal’s life: Mating here, mating there.

But at some point, you may begin to think you missed out. This is not my experience. In The Sense of An Ending the woman cries to her friend, “I just never loved.” It’s a very Western concept, but maybe there is something to it. When you romanticize about the past, and the present is no longer interesting, you may say to yourself, “I missed that moment of passion.”

DBN: In My Brilliant Daughter, the father bumps into a woman he once planned to run away with.

MGV: This story links back to my novel No New Land. Sometimes the relationship you had back home somehow doesn’t seem to work in the new country - a place where you are exposed to so much more. The last sentence of No New Land shows him looking at the CN Tower which symbolizes the world he could have gone out into. But he didn’t.

It’s all about growing old; growing older. These things come back to men and women. They ask themselves, “What could life have been like?” Which, of course, is the wrong way to think about it.

DBN: Is it? Why?

MGV: Because you have to make do with what you have now and what you are now.

DBN: While My Brilliant Daughter links back to your novel No New Land; The Way Stop links back to your memoir And Home Was Kariakoo. In The Way Stop you take a true story about traveling with a friend to a small Tanzanian town and transform it into fiction. The tale begins as a travelogue, evolves into a romance, and concludes as a thriller. Technically speaking, how did this happen?

MGV: I don’t know. Since I wrote that scene in Kariakoo, I remember feeling it would be wonderful to just get lost. I have these fantasies of getting lost.

DBN: What does the fantasy involve?

MGV: Just getting lost somewhere I don’t get the news; where my phone doesn’t work. Where I can’t hear from relatives or about the stock exchange. Just being by myself and going somewhere to die. I thought I would explore that.

DBN: Is this the way your imagination generally works?

MGV: I generally begin with an idea. But what form it takes, I’m not sure. Often, there is something nagging at me, for one year, two years, three years.

DBN: That long?!

MGV: Yes. For example, the idea for my novel Vikram Lall, had been with me for a long time. Also, the novel I just submitted, about a physicist. But not like me. A genius.

DBN: Like you, then.

MGV: No, no! It is the imagined life of someone else. Anyway, the idea had been with me for a while: How can a person - who is a great physicist by any standard - be a devout Muslim? On the one hand you believe a few equations explain everything; on the other you bow down to God. That thought has always boggled my mind. The novel is finished. It’s with a publisher now.

DBN: A powerful spirituality and Indian romanticism pervades much of your work. The story Speak Sweet Words, Softly, for instance, could almost be a prose poem.

MGV: There were dozens, maybe hundreds of variants of the Indian devotional form in medieval times. You still have the form today, but in the 14th and 15th centuries you had many more variants. The songs contain spirituality and some basic worship of a guru. These are songs of intense devotion in which the devotee is a woman. But a man can also take on the persona of a woman. So, there is this relationship in the songs between lover and loved.

This is the tradition the woman in Speak Sweet Words, Softly belongs to. Only she takes it further: She meets the guru who is so handsome that she actually falls in love.

DBN: Do you write poetry?

MGV: I edit the poetry at Mawenzi House. Once in awhile, I send queries to poets about word choice, etc. I do have a poetic sensibility. And when I first came to Toronto I did try for a few months to write poetry. That was at the beginning of my literary career.

DBN: The narrator in the story An Epiphany describes what it means to be approaching the end of a career. He sounds quite jaded. What are you feeling at this stage of your literary career?

MGV: I feel new trends have come to the surface. New fashions. I feel I belong to the wrong race. Neither white, nor Black nor Aboriginal. I feel I am older and easy to attack because I am not Ondaatje and not Atwood. It shouldn’t matter and it doesn’t in one sense. But I sometimes wonder if it is worth doing anymore. But then, what would I do? When I was an undergraduate, I was being offered graduate engineering at Yale. A professor wanted to recommend me to Harvard. But I was very obstinate. I said I want to do nuclear physics. So I went to do my PhD at Penn. I sometimes tell my wife we would have been so much wealthier if we had settled in the United States. But she says no, we are better off in Canada.

This interview took place on July 7 at a restaurant at Avenue Road in Toronto.