Independence by Cecil Foster

Independence by Cecil Foster

Independence is a tribute to classic Bajan literature. It places Foster in the upper echelons of Caribbean writers.

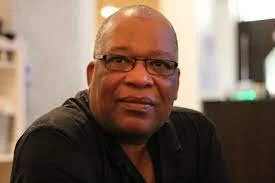

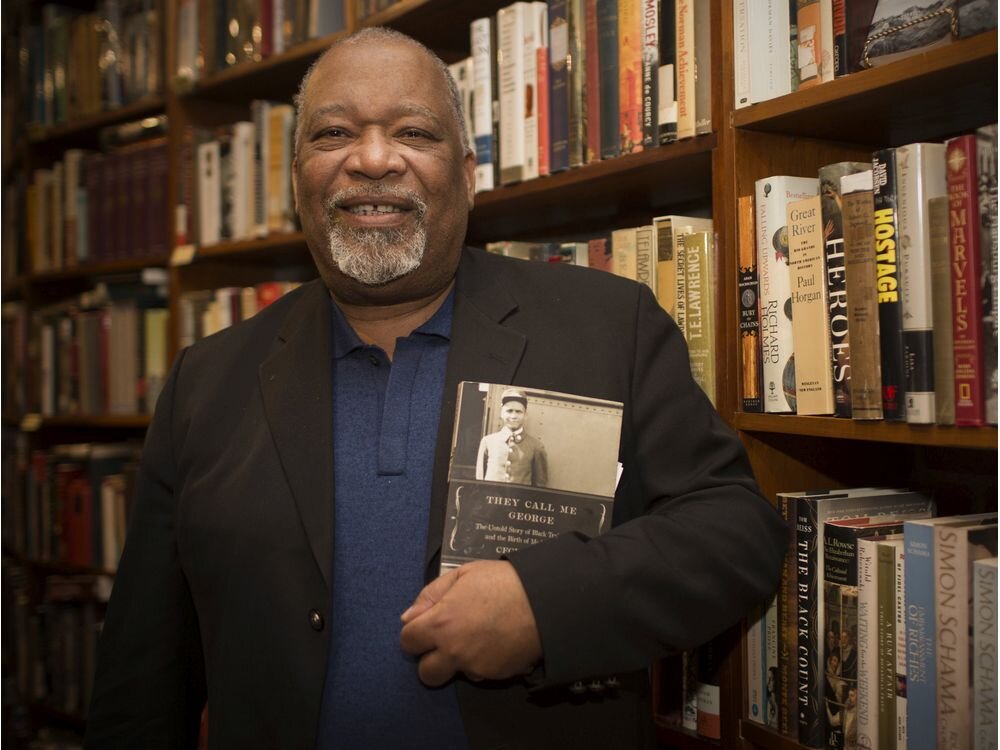

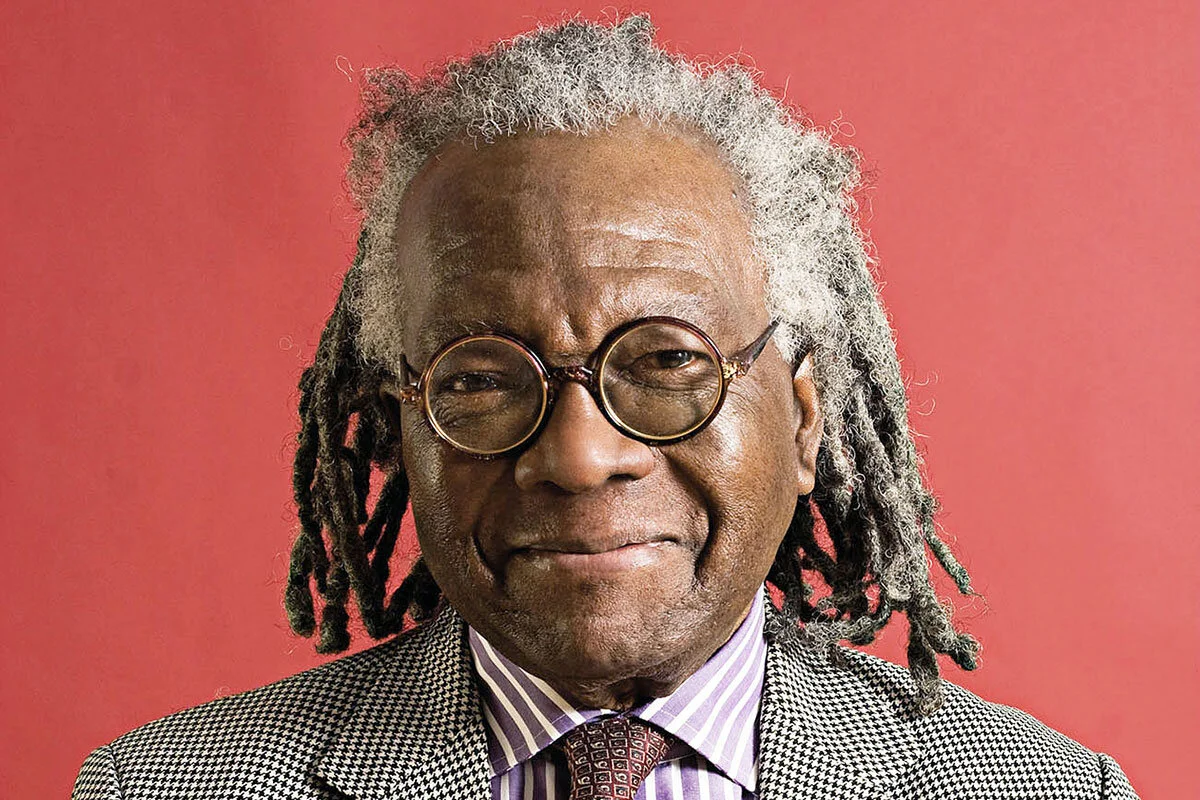

Growing up in, Bridgetown, Barbados, where he was born in 1954, Cecil Foster much preferred cricket to reading. Nevertheless, once a week his teachers marched him to the library where he and his classmates looked for the skinniest volume they could find. That is how he came upon Amongst Thistles and Thorns, Austin Clarke’s autobiographical novel about coming of age in Barbados.

Foster told me this tale for an interview for Maclean’s heralding the publication of his book A Place Called Heaven: The Meaning of Being Black in Canada in 1996. I remember going to his house in Thornhill where I set up my tape recorder in the living room. His three sons were playing in the background. His soon-to-be-ex-wife was there, too. She looked singularly unimpressed by the presence of one more reporter to celebrate the burgeoning literary career that was driving them to the poorhouse.

I enjoyed being in his presence. He had a sincere regard for the experiences of black women that I found extremely comforting. And also, he was a delightful tall tale teller. I mean that literally. When he sat on the couch and propped his feet up on a chair, his legs went on forever. That day, we talked about the childhood experience that has shaped his life and his art: His parent’s emigration to England to make a better life. They left Foster and his brothers in the care of his grandmother when he was two years old. He waited for them to send for him, but they never ever did.

He reworks these facts yet again in Independence, his glorious new novel, by far his best effort to date, outshining even his memorable debut, 1991’s No Man in the House. It opens in the village of Silver Hill in Barbados in the early days of the newly independent nation. There, 14-year-old next-door neighbours Christopher Lucas and Stephanie King are being raised by their deeply religious grandmothers while they wait hopefully to join their mothers in North America. But they have not heard from their mothers for years.

With Independence, Foster elegantly equates the coming of age of his protagonists with the coming of age of the nation. At the same time, he interprets that enduring theme so aptly articulated in the writings of critic Wilfred Cartey:” I going away. I going home.”

Foster’s own literary career dramatizes this trajectory that not only joins him to Clarke but also to Bajans George Lamming (In the Castle of My Skin) and Kamau Brathwaite (The Arrivants), two of the region’s most influential writers. Indeed, Foster dedicates Independence to Bim, the popular literary journal edited by Frank Collymore to which these men contributed and to which this novel owes a great debt. It was Brathwaite and Lamming who early explored the breadth and complexity of the Caribbean emigrant experience; an experience that turns out to be about much more than resettling abroad, but engulfs a history of cultural alienation beginning with slavery, incorporating colonialism and including the difficulties of acclimatizing after returning “home.”

In the novel Christopher and Stephanie, best friends from childhood, are forced to become independent of one another. They are raised in impoverished households that afford them little more than love. Schoolwork, church and shared chores regiment their week. Classmates poke fun that they are “grandmother children”: They wear modest clothing, sport old fashioned hairstyles and know to steer well clear of the dancehall. Polite and obedient, Christopher and Stephanie await the call from the mothers who are over’-n’-away.

In Barbados sports and education are the twin tickets to success and, as the school’s gym master preaches, they play an integral role in the process of both nation building and character building. Christopher’s skill as a cricketer draws local attention. For her part, Stephanie is a champion runner. Things change for Stephanie after Independence, however, when a neighbour, Mr. Lashley, becomes her “benefactor.” He returns from Canada, lavishing Stephanie with favour, including access to his colour TV.

Once again, there is no man in the house. Women are both tender caregivers and struggling providers. Christopher sees females as smarter, more reliable and more resourceful than men. Indeed, his grandmother pools her assets and energies with Stephanie’s to raise turkeys and pigs and to prepare souse to sell at the rum shop Saturday nights. The women’s great faith endows them with strength and wisdom. At the same time, it is their religious naivety — shackled to dated ideas — that imperil the children, especially the girls, whom they adore.

With strokes firm, but gentle, Foster etches a specific time and place. His world arises through a series of oppositions. While women are in the house, men are on the cricket field or in the barbershop. Or at the rum shop as opposed to Pastor Wiltshire’s outdoor services where hymns compete with the pounding beat of the dance hall.

Foster’s minute recording of mundane chores, especially food preparation, reminds me of Austin Clarke, as well as the wonderful Bajan writer Paule Marshall (Brown Girl, Brownstones). His descriptions of simple objects — including his grandmother’s drinking tot — are odes to the ordinary a la Neruda.

His ear is even better than his eye. The pitta patta of rain on the galvanized roof; the beating of waves on the beach; the Bradung Crassshh of a glass chimney; the decisive Bram! of a precipitous end and the Belang!Belang!Belang!Belang! of the sports master’s bell. All this produces a percussive symphony, which is mere accompaniment to the voice of Grandmother Lucas: “Just look at you. Sharp as a tack this bless’ed morning … Hair greased and brushed, with the part to the side of yuh head, uniform clean and ironed, yuh two shoes shining like ram goat stones, yuh belly full.”

“Politicks,” cricket and especially emigration round out this ongoing conversation, this unbroken island song circling round Christopher’s head. “We as a special people always on a journey,” says Stephanie’s grandmother. “We are a sojourning people. Like back in Africa, when we had a Garden of Eden… The next thing all o’ we like you and me living in this land here, brought out of paradise into a land of bondage, and we have never been able to get back. Not since that day.”

Foster’s words forge diasporic connections. The salt cod Christopher’s grandmother serves Saturdays hails from Nova Scotia. Men like Lashley return from the migrant overseas worker program in Canada and the U.S. to seek their share of the Independence dream. Independence, then, belongs to the multicultural project Foster pursues in books like 2004’s Where Race Does Not Matter, his exploration of exile in the novel expanding our understanding of the experience that profoundly shapes Canada’s present and past. Independence is a tribute to classic Bajan literature, placing Foster in the upper echelons of Caribbean writers, fine company indeed. This is a wonderful book, hopefully destined for wide readership and endless love.

This review previously appeared in the National Post.