The Passions of Austin Clarke

The Passions of Austin Clarke

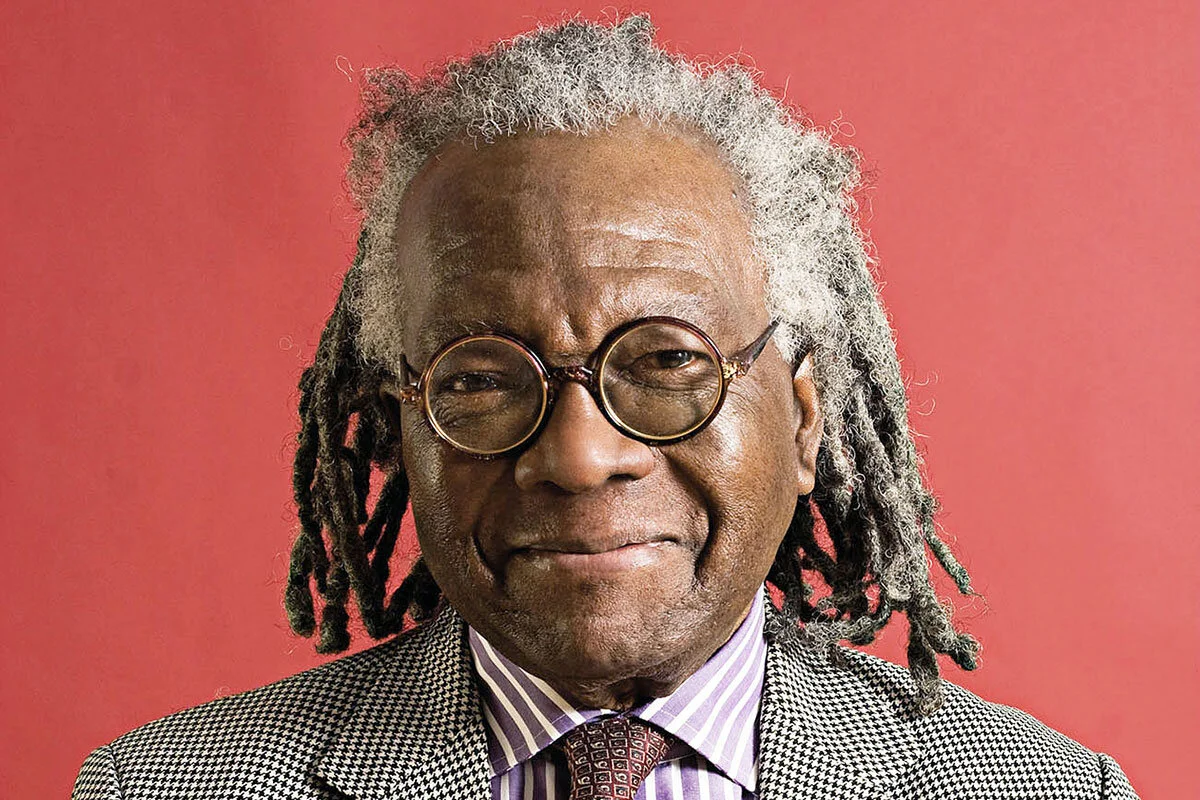

When Austin Clarke passed away in Toronto in June of 2016, the news was broken by Barbados’ The Nation. It seems fitting that the death of Canada’s pre-eminent black writer was first reported in the land of his birth: the culture that sustained his spirit and imagination.

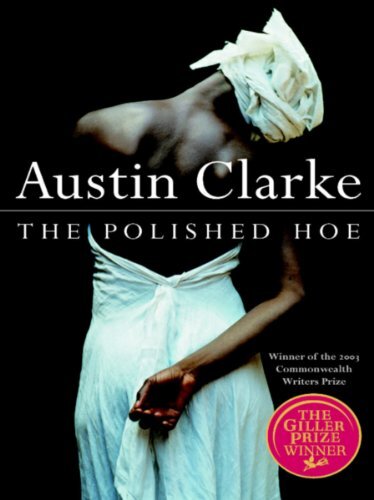

His most famous book, The Polished Hoe (2002), was the story of the sexual exploitation of an island woman. It brought him the Scotiabank Giller Prize and marked the apex of a literary career that spanned more than fifty years. Clarke’s extensive oeuvre—nearly a dozen novels, several story collections, as well as memoirs and poems—feature Bajans at home or West Indians in Canada. His characters battle the outer challenges of colonialism, racism, and economic hardship and the inner challenges of colonial mentality and racial shame. Yet he manages to evoke their wit and resilience through an exuberant Bajan language. Clarke believed that language—specifically, vernacular—was the most significant aspect of his narratives. “Vernacular is the lingua-franca of Barbados,” he told me in 2003. “[O]ne can no longer deprecate this language by calling it a dialect.”

Clarke’s early works including The Survivors of the Crossing (1964), Amongst Thistles and Thorns (1965) and the novels that comprise his Toronto trilogy: The Meeting Point (1972), Storm of Fortune (1973), and The Bigger Light (1975) offered a rare reflection of black Canadian lives. He described the hyphenated reality of individuals caught between cultures in ways that resonated with millions of immigrant readers. His novels, from the start, were quintessentially Canadian, among the first to imaginatively contemplate the new ideal of multiculturalism. What’s more, they began to appear during America’s Civil Rights Movement, forcing Canadians to extend the conversation of racism beyond self-congratulatory accounts of the Underground Railroad.

Clarke was born in Saint James, Barbados, on July 26, 1934, to a hardworking single mother and an absent artist father. Like most black Bajan families at the time, he and his mother struggled financially. Clarke excelled at academics, winning a place at prestigious Combermere secondary school and moving on to elite Harrison College. He gained renown as a national track star.

He came to Canada in 1955 and enrolled at University of Toronto for English. In time, however, dwindling finances forced him to abandon his studies. After leaving he toiled away at a series of menial jobs that he described as “work black men could get.” Desperation eventually drove him into the Toronto offices of Thomson newspapers in December of 1959. By this time he had a wife and child. He was ecstatic when Thomson hired him for the position of reporter in Timmins, Ontario—until he learned that his new job was located hundreds of miles north of the city. “When I got to Timmins,” Clarke recalled in an interview for Publishers Weekly, “It was the 23rd of December. I went to work and got an advance of $35. The boss had left a Christmas card with a $5 bonus and a loan of $50 that I could pay off one dollar a week.”

Journalism eventually led Clarke to freelance employment with the CBC and the chance to realize his dream of visiting Harlem. It is here that he conducted the now famous interview with Malcolm X that many white listeners described as incendiary. In one memorable moment, Malcolm X addressed accusations that Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad advocated hate. “He teaches black people to love each other. He teaches black people to respect each other,” says Malcolm X. “Just because he doesn’t waste his time telling his people to run around and drool at the mouth over white people, white people today accuse him of teaching hate.”

As a result of this interview, Clarke became known as the angriest black man in Canada. Although Clarke felt he could never survive the virulent American racism of the times—it’s one of the reasons he chose to live in Canada instead—he deeply admired the country’s civil rights activists.

Clarke's CBC interview with Malcolm X: A fearless exchange between two brilliant Black men

Harlem more than lived up to Clarke’s expectations, especially when it came to music: “Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Art Blakely, Thelonious Monk, Sarah Vaughn, Nina Simone.” Clarke chanted to critic and novelist H. Nigel Thomas. “To be able to go to Harlem on a Friday night and sit in a room and listen and watch these musical giants play. I always felt this was essential,” said Clarke. “That there could not be a successful civil rights movement that excluded culture . . . Even though life for black people was brutally, explicitly racist, our souls were enriched, we were warmed by the expression of beauty by our artists. “

Clarke is often described as a literary outsider. I am not sure to what extent this was true. He was certainly the only major black Canadian writer publishing in the 1960s and he most definitely experienced the chill of Canadian racism. Yet he was published quite early in his career by the larger houses, even though dissatisfaction caused him to change publishers regularly. He was also invited to teach at Yale and Harvard—an uncommon honor for a Canadian writer in those days. What’s more he belonged to an influential literary circle that included Margaret Atwood and Barry Callaghan who were fostering a homegrown Canadian literature.

If Clarke’s literary fortunes tended to waver it was partly due to his straitened financial circumstances—the challenge of raising children on a novelist’s earnings—and partly due to his preoccupation with politics. For a while he served as managing editor of Contrast, Toronto’s flagship black newspaper, where he encouraged young writers and urged black readers to political action. He led marches against apartheid and spoke out against police brutality, an issue he would speak to explicitly in future works like In This City and his final novel More. In addition, Clarke served as cultural attaché to Washington for Barbados in 1973 and then returned to the island to head up the Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation. In 1977 he took a run at Ontario politics as a member of the Conservative Party. From 1988–1993 he took a nine-to-five job with the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. He later told me he would never forget the cruelties endured by many of the female refugees.

Though Clarke’s novels are not strictly autobiographical, his subjects largely follow the trajectory of his life. The Toronto Trilogy about West Indian newcomers to Canada was written when he was a newcomer to Canada. The Prime Minister (1977) about a corrupt Barbadian government was written after his dispiriting stretch with the Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation. Likewise, The Origin of Waves (1997) about two boyhood friends from the Caribbean who run into each other in a Toronto snowstorm was written after Clarke had lived in the city for forty years.

I still remember going to his house to interview him for that book. He lived on McGill Street then. It was late February and his Christmas tree was still standing. He explained that he kept it up all year because he so loved Christmas. Maybe that’s what warmed me to him. Or perhaps it was the delicious crumbly Christmas cake he served or maybe the tea poured fastidiously into a bone china cup. Over the years we met many times. He gave me good advice. “Nurse!” he once said early in my career, “Be prepared to face racism in the literary world.” He then added firmly, “I am not telling you not to love. Understand?”

Understood. I know that for Clarke, love was the critical factor. It was the quality that most informed his life and his work. It explained his exquisite literary mindfulness. I remember asking him about writing The Polished Hoe, about his knowledge of the tiniest details. How did he know, for instance, what the road was made of; or why it smelled the way it did? And how did he recognize the exact components of a sound the heroine hears? And where did he learn the precise method a woman from that time and place might use to cook a chicken?

“It’s instinct,” Clarke explained. “I know so much because I love the situation. I love the geography of the place. I love the people inhabiting the place. I love the condition of the inhabitants. So there is very little for me to do apart from observing. Even though I’ve lived abroad from Barbados, I am still able to recreate the Barbadian sensibility in the novel. And that comes from a longing to belong. And a serious passion for language.”

Austin Clarke meets Queen Elizabeth II

Clarke will be sorely missed by his family, his devoted readers and the innumerable writers he encouraged, edited and mentored despite the demands of a hectic schedule. There is hardly a single black Canadian author he did not assist in some way. “He was always a source of ideas,” says Bajan Canadian novelist Cecil Foster. “He was always willing to share with me the unvarnished truths of what it means to be a black writer in a Canadian industry where blackness is an exception among agents, editors, publishers, publicists and reviewers. He would say our task was to be patient while we keep explaining and teaching our perspective. By persevering against the odds, he taught the host of writers that flocked to him that, while it will be difficult, we too can triumph.”

An earlier version of this piece appeared in The Walrus in 2016.