Should We Write About Slavery?

Should We Write About Slavery?

I get a little exasperated when people discourage me from discussing the topic of slavery during Black History Month. For one thing, we hardly know anything about that ad hoc, hodgepodge, utterly random collection of customs and laws cobbled together to brutally maximize the wealth and power of White people. We know virtually nothing of how that institution operated in North America, and even less about enslaved people – individuals who were kidnapped and held against their will. Every one of whom had their own gifts, their own frailties, their own passions, their own hatreds, their own loved ones, their own presence, their own pasts, their own stories. The word slave has been used as a giant eraser to blur the details of millions of Black lives - that mattered.

We rarely learn that Africans were sought after for their brainpower as well as their manpower: In Maryland, for example, White planters coveted Africans of Asante heritage for the knowledge of agricultural practices planters themselves frequently lacked; while African expertise in shipbuilding and navigation facilitated the efficient transport of goods along the Eastern seaboard, enhancing their owner’s ill-gotten gains.

And about those Black seaman -not all were enslaved, just as communities of free Blacks existed in perilous proximity to their slave-holding neighbours. It was not at all unusual for a free Black woman to be married to an enslaved man. Or vice versa. If a free man was married to an enslaved woman, their children- his children- belonged by law to his wife’s master.

Which is to say that if your mother was a slave, you were a slave as well. But what if your father was a White man? In fact, what if he was the master of the house, which was frequently the case? Well, if he possessed a conscience, he might tacitly claim you and send you North to be educated. It was much more likely, however, that he would keep you toiling on his plantation, never acknowledging his painfully obvious paternity, nor the unspeakable circumstances of your birth. Slavery was social chaos.

That most Black people have learned next to nothing about slavery constitutes an alarming gap in crucial knowledge about our selves. And without that knowledge I don’t see how we can move confidently forward. And to be honest, I don’t see how we can even move confidently backward- in time, I mean – to a proper comprehension of Africa’s rich and powerful history including the Songhai Empire, the Mali Empire, the Ancient Egyptian Empire- I could go on; back, as well, to a deeper knowledge, of a scandalously hidden past involving a Black presence in North America long before the slave trade.

Certainly, it would be more pleasant to focus on the high points of Black history and forget the lows. It can be traumatic to consider the cruelties slaves faced - the incomprehensible barbaric violence perpetrated by White people upon their Black bodies. We sometimes forget, however, that their trauma does not belong to us: We are not the ones who actually suffered. At the same time, enslaved people were much more than the embodiment of black pain. They were human beings who lived and loved despite the racist challenges they faced every day - a circumstance with which 21st century Blacks should be able to identify.

******

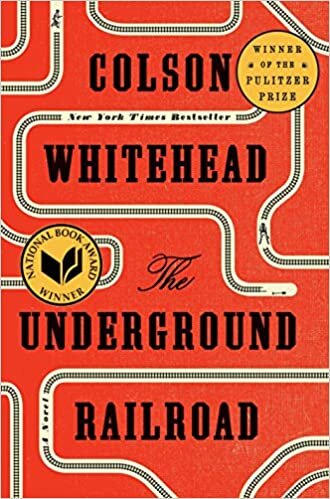

I am so grateful for novelists who remain undaunted by the word “slave.” My series “Should We Write About Slavery?” includes pieces on novels by Marlon James, Andrea Levy, Colson Whitehead, Lawrence Hill, Esi Edugyan, and Toni Morrison. In each of these novels the authors share their distinct visions and literary interpretations of Black life during a brutal historical era.

First on my list is Jamaica’s Marlon James, best known for his Booker-winning novel A Brief History of Seven Killings. James’s previous work, The Book of Night Women, is equally engrossing. Set on a Jamaican plantation in the 1780s, it features a group of enslaved women who conspire to exact revenge on their violent plantation. To tell his story, James adopts the style of the revenge tragedy, a dramatic genre popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. He also draws on traditional Western myths, giving his characters names like Lilith, Paris, Circe and Homer. He transforms our enslaved ancestors into archetypes and their narratives into epics.

The late British author Andrea Levy famously used humour to tackle the uneasy topic of race. And she did not see fit to alter her approach when it came to writing about slavery. The Long Song, her parody of life on a Jamaican plantation, centers upon the hilarious July, a slave who embarks on a passionate affair with her master. In an interview Levy explained to me, with characteristic audaciousness, why she chose to make people laugh about slavery.

The diasporic reach of Lawrence Hill’s The Book of Negroes influenced many slave novels that came after it. His heroine, Aminata Diallo, is born in Africa, sold into slavery in the Carolinas, achieves freedom in Canada and returns to Africa. This astonishing trajectory for any one life was not unheard of in slavery times. Hill’s slave narrative is notable, too, for introducing Aminata before she is kidnapped. Because we know her father, a jeweler, and her mother, a midwife, we more intimately feel her loss. I spent some time talking with Hill at the Calabash Literary Festival in Jamaica. It got me thinking about the impact of his ground-breaking work.

Esi Edugyan’s Giller-award winning novel, Washington Black, also travels enormous distances. Her eponymous hero, an escaped slave, journeys from Barbados to the American South, to the North Pole, and to Canada, England, and Africa. But when I called her book a slave narrative, Edugyan begged to differ. I was interviewing her onstage at the time (I will post a link to the video) and I did not quite grasp her point. Since then, however, I have come to agree with her perspective. As Washington Black escapes bondage early in the book, he can no longer be referred to as a slave. In that light, not only Washington Black, but The Book of Negroes, Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, Beloved as well as many real-life accounts are not slave narratives at all. Rather they are tales that chronicle what happens when a formerly enslaved Black person attempts to carve out an autonomous existence in the “free” world. Part of what distinguishes Washington Black from other novels of its kind is its sweeping 19th century context- both in terms of history and in terms of classic literature. The book sits comfortably on the shelf beside Jane Eyre, Frankenstein and Moby Dick.

Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad features Cora, an escaped slave from Georgia, who is racing towards freedom with a slave-catcher hot at her heels. Full of suspense, adventure and strange vistas, the book reads like a compelling episode of The Fugitive or Star Trek. Whitehead’s approach is a little sci-fi; his vision, fantastically dystopic. His underground railroad, for instance, is an actual subterranean train that makes a series of macabre stops along the route to freedom. For Whitehead, slavery’s historical evils were so wickedly outrageous, they naturally conform to notions of the fantastic and grotesque.

Readers and critics alike view Beloved – the story of a fugitive slave who murders her child- as the quintessential slave narrative. Consequently, Toni Morrison’s other slave novel, A Mercy, tends to get overlooked. It is an exquisite tale in which an enslaved mother pleads with a kind man to purchase her daughter in order to remove the child from a depraved plantation household. Thus, Jacob Vaark of New Amsterdam becomes a reluctant slave owner. Where Beloved opens in the decade leading up to the end of slavery, A Mercy unfolds in the 1600s as the practice begins to take hold. The Black girl, Florens, grows up on Jacob’s farm, sharing the workload with an addled White girl, an Aboriginal woman and two indentured servants. In her teens she falls in love with a free Black man. Her life spins out of control when she encounters a group of Puritans who treat her with physical disgust. Their profoundly racist rejection shatters her mind. Beloved is the story of what happens to a Black woman who escapes slavery. A Mercy is the story of what happens to a Black woman who begins to see herself as a slave.

Over the next couple of weeks, I will post pieces on the books discussed above, splendid novels that insist there are numerous ways of writing about slavery – as numerous as the enslaved people whose stories remain untold.

Sincerely,

Donna