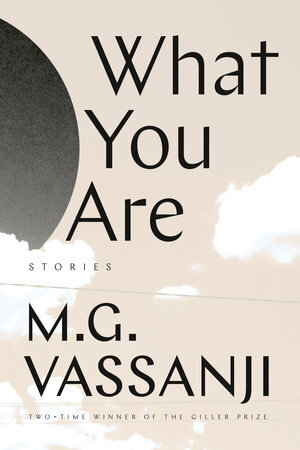

What You Are: A Candid Conversation with M.G. Vassanji

What You Are: A Candid Conversation with M.G. Vassanji about Family, Forgiveness and Race

PART 1

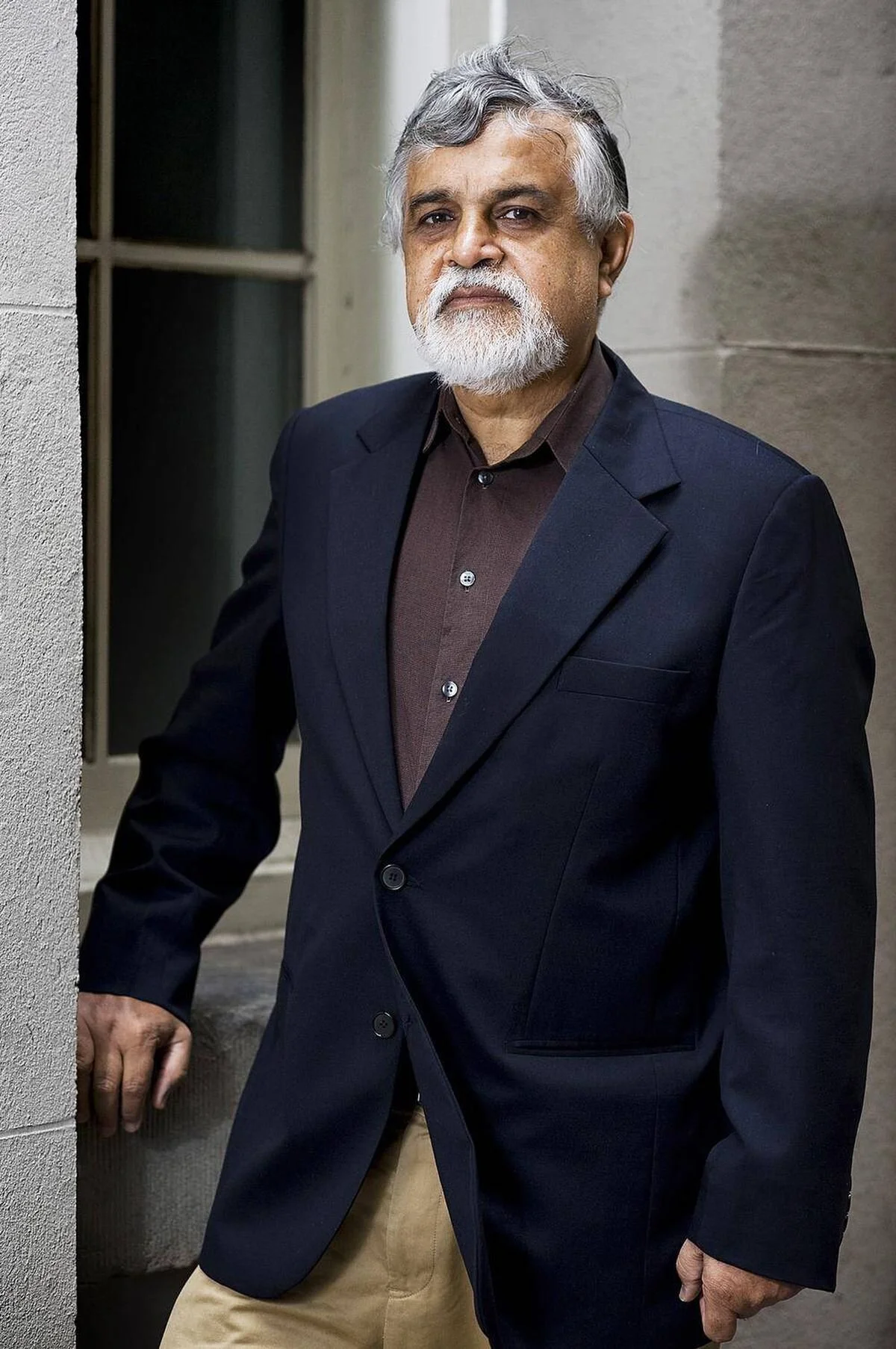

I relish every opportunity to speak with M.G. Vassanji, one of Canada’s most internationally esteemed authors. Vassanji has won two Giller prizes: The first for The Book of Secrets and another for The In-Between World of Vikram Lall. He also received a Governor General’s Award for A Place Within: Rediscovering India. These titles represent the tip of the iceberg: Vassanji’s entire oeuvre is rich in beauty and wisdom. His latest book is a collection of stories called What You Are, which hints at a preoccupation with racial and religious conflict and identity. Many of the stories feature a South Asian-Canadian population firmly embedded in the national mosaic.

Vassanji sometimes describes himself as the perennial outsider: An Asian in Africa, a Muslim in India and a brown man in Canada. But it is precisely this tapestry of histories, cultures and traditions that nurture his unparalleled insights into the human heart. I recently met with Mr Vassanji for lunch at a restaurant on Avenue Road in Toronto. Well before I turned on my tape recorder, the conversation was off and running.

_________

MGV: Where I come from, Dar es Salaam, we believed in unity and in a common identity that included our differences. In India there can be hatred (between Hindu and Muslim). But in East Africa – especially Tanzania - there wasn’t hatred. There was difference. There was some racism. But that racism - after Independence - it somehow went away.

DBN: There are not as many Asians in East Africa today. Is that not because of racism?

MGV: But from which side? After Independence Africans were the majority. They didn’t have anything to fear from the Asians.

There will always be someone nasty. There is racism everywhere. Or communalism. Or religious differences. You cannot escape it. It will never be perfect. If I go to India, they say “You are Muslim”. If I go to East Africa, inevitably someone will say “You are not indigenous African,” and here in Canada, of course, I face the same thing. It really bothers me.

DBN: The title story in the book, What You Are is about a young woman who finds out she is adopted. Zakia takes great pride in her African American heritage. She is dismayed to learn that her biological mother was a poor Hindu girl, a single mother, from Tanzania. Why did you call the story What You Are and why is that the title of the collection?

MGV: The title came to me because of the story. People talk about adoption and searching for their real parents. And I always think, they are already with their real parents. Your real parents are the ones who brought you up.

DBN: If biology means nothing, why tell us Zakia’s biological grandfather was a cobbler and that her shoes never quite fit?

MGV: I’m not sure why I added that detail. (Laughing). I guess I was admitting Zakia is a little bit different from the rest of the family. But it is not something important. Zakia only remembers her ill-fitting shoes after she learns she is adopted.

DBN: One of my favourite characters in that story is the African American father. His real name is Martin but in Tanzania he is given the nickname Baraka. He’s like a cross between President Obama and the poet Amiri Baraka. Just as suave, with much swagger.

MGV: Yes. Everybody loves the Martin/Baraka character. Baraka is a Swahili word that means blessing. And it seemed like a good name for this character just as it is the perfect name for President Obama.

DBN: What You Are focuses on your most important theme: That we are all the same.

MGV: Yes. We are all the same: That is a motto for me.

DBN: Your work has always struck me as unique in terms of fellow feeling; human feeling. In other words, your sincere belief that all people are the same, is different. Does this ever make you lonely?

MGV: Yes. I am a very lonely person. You feel you are at odds with the world in the sense that people take easy answers. Or fall into nostalgia. They believe anything. To be a writer you are always looking within yourself - all the time. You are really gutting yourself and you live with that. It’s a lonely process. I’ve been lucky. My wife has supported me and put up with a lot. She understands.

DBN: Another important theme in your work is forgiveness. In the story, My Brilliant Daughter, a selfish sister refuses to forgive her brother for who knows what exactly.

MGV: I find it so mind boggling: siblings not getting along. Two people playing together throughout their childhood and suddenly they become enemies! How do you explain that? Or how do you develop an antipathy to your own mother? I cannot fathom it! I can only say that as you grow older, as you face your own mortality- or your parents’- you realize. You can’t make enemies of your own siblings and mother. But people do that all that time.

DBN: Forgiveness comes up again in An African Problem in which two Tanzanian men arrive in Toronto to track down a Rwandan war criminal. One character in the story applauds Black South Africans for forgiving their white compatriots. But another character questions whether Blacks have truly forgiven after all. The scene reminded me of how annoyed I was when Nelson Mandela began forgiving people willy-nilly, after he was released from prison.

MGV: But that is why the West loves Mandela. There have been so many great African leaders: Nyerere; Kenyatta-who had his problems, but was a great leader- and Nkrumah. But the West doesn’t want them. They always want a “good” one.

DBN: What were you thinking about forgiveness when you wrote An African Problem?

MGV: I believe in forgiveness - not forgetting. And, also, a genuine kind of atonement. You can’t forget. And you cannot just accept. But you are not going to take this bitterness forever.

DBN: Gulnar in A Shooting in Don Mills is sexually assaulted. She never forgives.

MGV: You have to understand the hurt Gulnar carried for 20, 30 years, coming from a culture where a woman who is raped might even commit suicide.

DBN: But she has this magnificent faith. She is a devout Muslim. The Christian faith, for example, says you must forgive.

MGV: Christianity is very focused. The faith Gulnar grew up with is more devotional. I don’t think it has a moral message per se. It’s devotional. You are just supposed to be good. But when a crisis comes – the response is not like with Jesus Christ, to turn the other cheek. I don’t think that teaching is there. Mainstream Islamic faith tells you to fight for your rights, and to fight injustice.

DBN: That story was so surprising. It was not something I would have expected you to write.

MGV: Maybe it’s because I was brought up by three women. My mother and two sisters. For me there is a feeling of devotion, of protectiveness and an understanding of women. My mother was strong. You can see this in my depiction of her in the first story The Send Off. Sometimes I wish I had had a father to give me some toughness. (Vassanji’s father died when he was five).

DBN: I was also surprised by the depth of anger in the story – the racial bitterness. The cruel policeman is actually named Officer White.

MGV: I have an anger against the racism and racial injustice. The barriers we faced. I don’t always speak the same language- express it the same way as other people. Back home, we had some excellent British teachers- better than the Indian ones. My anger is not toward these people who I really respected and who were very nice. They knew exactly what to teach us to pass the O-Level exams. They knew the rules and they taught us the rules. But then the whole situation where you were the inferior.

Dar es Salaam city at dawn

In the U.S. it didn’t bother me. I was a student and they treated me like a foreigner, and I was happy to be one. I would tell them I’m from Tanzania and they would take an interest.

MGV: But coming here (Canada) it was very stiff. I think it’s much better today. Anyone who came here in the 1980s knows the difference. In those days Canadians even ate pizza with fork and knife! That was Toronto! The stiffness! The dressing up in the subway! Whereas in the U.S. and even in London, people were casually dressed.

Then there was the physics department at the (University of Toronto where he was a research associate). The way some professors behaved! Not all. The guy who hired me was an Englishman. He was very nice- very generous. But there were others. In those days, the physics department was almost all white. Whereas if you went to MIT you would see all the Chinese and Indians already arrived.

MGV: You know when they talk about microaggressions? Give me two minutes and I will give you ten instances of what I suffered through with my wife. We moved into an Anglo area. We liked the way the houses looked, the quiet street and the trees. One day when my wife was in the garden someone passed by and said to her, “How did you end up here?”

And of course, the sullen looks when we went to the European deli on Yonge Street, two minutes away from our house. Or when I took my son to the Conservatory for his music lesson. I remember this young boy started making faces at me. I thought, “Would he do that to a white man?” Once when my son’s piano lessons were in our neighbourhood, I saw a space clear of snow where I could park and wait for a half hour or so. While I am sitting in my car this guy comes up to me and says, “This is my area and my spot.”

“But it’s a public area,” I said. He glared at me. “You little man,” he said. I swear to you, I am a very peaceful person, but I am glad we have gun laws here. If I had a gun in my glove compartment, I don’t know what I would have done. The thought still comes to me 20 years later.

DBN: All of this hurts my heart. I don’t know if white people realize the depth of the pain they cause.

MGV: There’s a presumption in them that we are of less consequence. I remember that not long after we arrived in Canada a South Asian guy was thrown onto the subway tracks.

DBN: I do remember that.

MGV: Last Saturday I was talking to a friend who reminded me about the white men who chased him into Castle Frank subway station. They threatened to kill him. When he asked the man in the ticket booth to open the gate, the guy refused. Luckily there were some cops nearby, so he was saved. My friend had a law degree from Tanzania. He took his assailants to court.

DBN: Speaking of lingering trauma: The subject of Indian Partition, more than 70 years ago now, crops up throughout the book.

MGV: People are not over it. Every family from Punjab has been affected. Even my wife’s family. Her father left Punjab just before Partition, a city called Amritsar. They had to escape overnight. Someone told them, “Leave! Gangs are coming!” They got into the train for Bombay. On the way someone stole their luggage. They reached Bombay without money or belongings. But at least their lives were spared.

My father-in-law never returned to Amritsar. But when I took the family to India, he told us to go there. A Sikh friend took us to the house where my father-in-law grew up. Across the street was a man who remembered the family. He told my wife that his sister had been close to her father’s sister. “Do you want to call her?” he asked. And this is the thing I will never forget. On one end of the line was my wife. On the other end of the line was this woman who had been childhood buddies with her aunt. And both women – who didn’t even know each other- were crying.

I Interviewed M.G. Vassanji at a restaurant at Avenue Road and Wilson on July 7, 2021. Part Two to follow.